Making Sense of DePIN Nonsense: Part 1

A Practical Primer on Infrastructure Finance and the Role Tokens May Play in Its Evolution

Thanks to Yoon Kim for his instrumental role in researching and writing this piece, and providing much needed momentum to hit publish.

This piece is focused on connecting the dots for non finance people and hopefully stimulating some engaging conversation on the future of the DePIN category as it enters a phase of disillusionment, with operators deploying millions in capex chasing an endlessly inflationary pool of magical internet money while lighting real cash on fire.

Today, the DePIN landscape can feel like a perpetual motion machine where people strap overpriced sensors to poles to earn memecoins. But there are also green shoots showcasing the potential for new models to aggregate, fund, and govern a wide range of infrastructure assets. At Crucible, we see the $100 trillion required to drive the global data center economy as a transformative opportunity to usher in the next wave of investment in the crypto ecosystem. We believe this will happen through innovative infrastructure financing models, blending credit and cash flow mechanisms. These efforts will be supported by decentralized networks that enable efficient coordination of virtualized services and leverage decentralized governance frameworks to ensure transparency and adaptability.

This series is a long-ish primer on the fundamentals of infrastructure finance and our perspective on how infrastructure finance might evolve when brought onchain and incentivized and governed with tokens.

Infrastructure Finance 101

Investing in physical infrastructure like power plants & communication networks - is radically different from investing in tech. Physical infrastructure has long planning cycles & investment timelines (decades, not years), beneficial tax treatment from depreciation, and other exogenous variables that can significantly impact the return profile of these investments. Once built, these assets offer investors predictable cash flows against their initial capital outlay in order to manage their ongoing operating cost (opex).

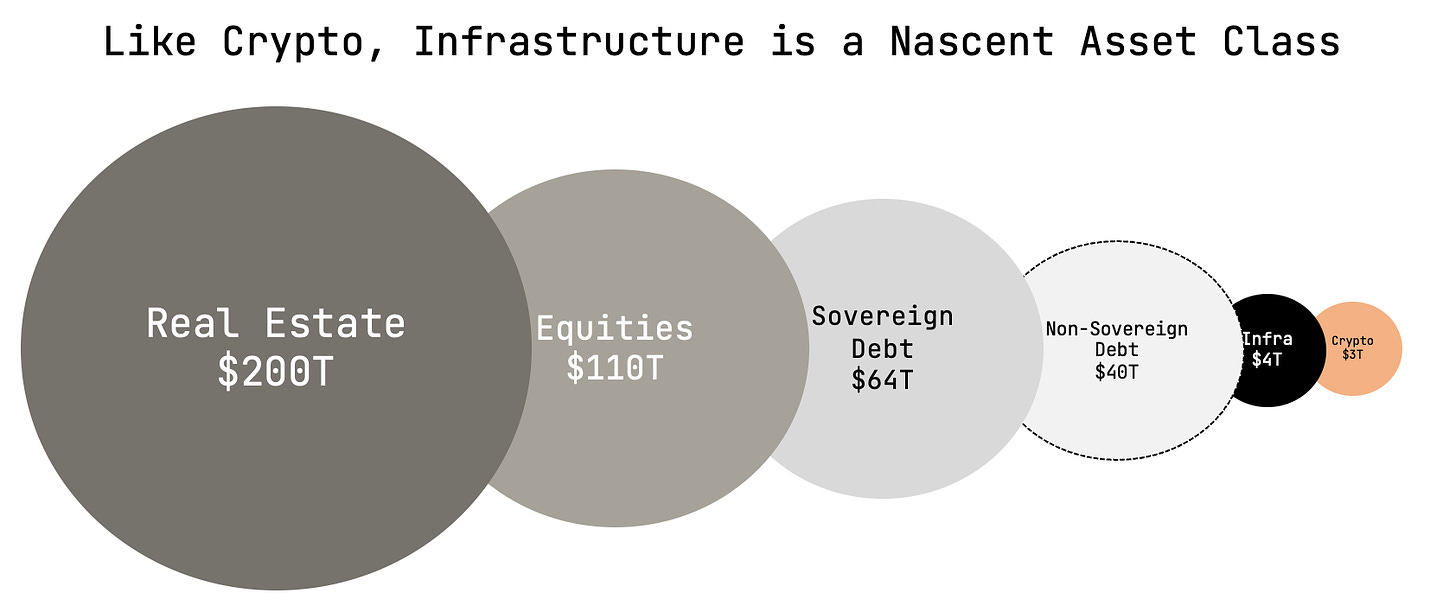

Infrastructure investing is an estimated $4T per year and this is expected to increase to $9T of annual spend over the coming decade as demand for energy, compute, and connectivity continues to grow exponentially. Infrastructure investing makes up only 4% of institutional investment portfolios.

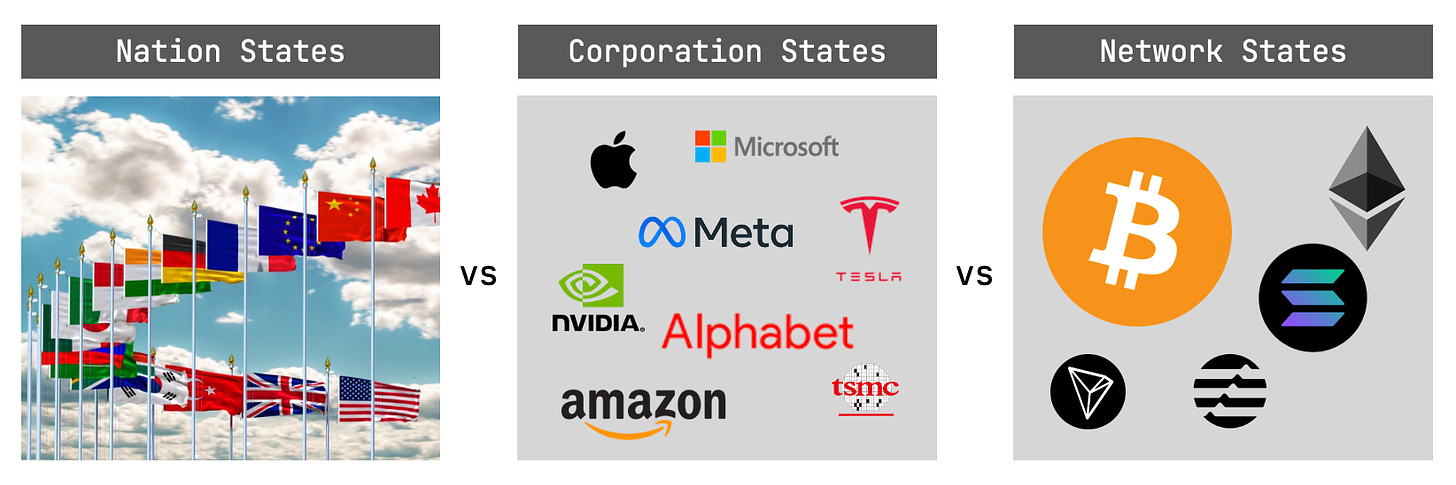

Historically, governments have been the driving force behind infrastructure investing, but this is changing. Governments are increasingly budget constrained. Private companies and funds are filling the gap. Hyperscalars are funding critical energy infrastructure to ensure they have the power needed to operate their massive datacenters. “Corporation states” are becoming infrastructure investors who make long-term capital investments to secure their own future. This tension between nations and corporation states (who have their own economies that rival that of G20 economies) is only going to become more pronounced as incentives diverge.

Along with corporates who need this infrastructure to keep growing, private infrastructure funds are emerging to fill the gap. Given the long duration mismatch between spending money and making money, infrastructure investing is especially sensitive to rates and pricing of risk. Just like tech investing is a specialized skill set, infrastructure investors rely on a specific methodology for funding these large-scale ventures that relies on the project's ability to generate cash flows for investors.

To evaluate these investments, investors need two basic models - CAPM and WACC - to evaluate the project’s financing structure and determine if these projects produce risk-adjusted returns across a wide range of macro conditions. Let’s put on our finänce hat…

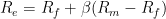

CAPM

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) determines the cost of equity for the project. CAPM helps quantify the required return for equity investors given the project's risk profile:

For infrastructure projects, the beta (β) often reflects:

1. The project's sensitivity to economic cycles

2. Regulatory and political risks

3. Technology and operational risks specific to the project

This model allows project sponsors to price the equity component of the capital structure, ensuring that returns are commensurate with the project's risk profile.

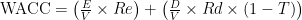

WACC

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is crucial in project finance as it represents the blended cost of capital taking into account both equity and debt:

Where:

E = Market value of equity

D = Market value of debt

V = Total market value (Equity + Debt)

Re = Cost of equity (derived from CAPM)

Rd = Cost of debt

T = Corporate tax rate

Here are a few important things to keep in mind:

1. The equity component (E/V * Re) typically represents ~20% of the capital structure, with the cost determined by CAPM. Most infrastructure operators have limited risk appetite to take down 100% of the financing. One reason bitcoin miners are publicly listed is because public markets allow them to access equity financing at low cost by issuing more stock. Many miners have a rate of equity of 10% or less. Venture capital equity has a cost of 25% or more.

2. The debt component (D/V * Rd * (1-T)) often comprises ~80% of the funding, usually at a lower cost than equity. Infrastructure finance markets are well established and tend to see rates tied to benchmarks like SOFR (SOFR = “secured overnight financing rate”). SOFR + 100 to 200 basis points is currently 6-7% yield. In an environment where the risk-free rate is 5%, debt gets more expensive because lenders must be compensated for the additional risk they’re taking.

3. The tax shield (1-T) can significantly impact the overall cost of capital, making debt financing attractive. In the US, the tax shield is also complemented by other incentive programs. One such program is the Opportunity Zone designation which allows investors to avoid capital gains taxes altogether by investing in economically disadvantaged areas for a period of 10 years or longer. It is no coincidence many Bitcoin mining facilities were built in Opportunity Zones.

Application of CAPM and WACC in Project Finance

Now that you’re an infrastructure finance expert, let’s discuss why these basic financial models matter when thinking about capital structure.

The core principle of project finance is that the asset is financed on a standalone basis which is amazing for a fund from a risk point of view as there’s no contagion risk.

In order to raise debt on a project only basis, the lender has to get comfortable they can get their capital back from the cashflows of the project, because the only security they have is over the contract of the project which often doesn’t include any land, which is different to the security position for real estate lending. Therefore, the cashflows must be predictable and under contract. Unlike venture, they don’t lend on “vibes” or growth plans. They need to see a signed contract with a credit worthy counterparty.

This approach allows infrastructure developers to create tailored financing structures to attract a wide range of investors with various risk appetites and durations. These structures align stakeholder interests while maximizing project success probability, enabling large-scale infrastructure projects that might be too risky or capital-intensive for any single entity.

Project Viability Evaluation

WACC serves as a hurdle rate for the project's Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Viability requires the expected IRR to exceed WACC for the project. If you’re buying hardware to support a DePIN network, the expected rate of return from operating that hardware needs to exceed the cost of buying and operating the hardware.

Risk Distribution

Infrastructure projects involve various risks (transmission delays, cost overruns, demand fluctuations). Project finance allows risk allocation among stakeholders. CAPM, through its beta (β), reflects the project's specific risk profile, determining appropriate returns based on assumed risks.

Capital Aggregation and Lower Cost of Capital

Project finance pools capital from diverse sources for large-scale projects. WACC helps set the optimal debt-equity mix, minimizing overall capital costs while maintaining an acceptable risk profile. Ambitious infrastructure projects like power plants, new transmission and distribution infrastructure, or telco networks are often too expensive and too high risk for one entity to finance alone.

Balance Sheet Optimization

Project finance provides an off-balance-sheet solution for operators, preserving financial ratios and borrowing capacity. WACC optimizes this structure by balancing lower-cost debt against higher-return equity.

Public-Private Synergy

Facilitates private sector involvement in public infrastructure, introducing efficiency and innovation. CAPM and WACC offer a common language for risk and return expectations.

Tailored Risk Management

Allows bespoke strategies (e.g., turnkey contracts for construction risks, take-or-pay agreements for demand risks). These strategies impact CAPM's beta, affecting required equity returns.

Cash Flow-Centric Financing

Capitalizes on predictable revenue streams, aligning repayment schedules with expected cash flows. This predictability often lowers CAPM's beta, potentially reducing equity costs.

Putting it All Together

Project finance, supported by CAPM and WACC, provides a framework for talking about risk and return as it pertains to financing decisions related to large scale, long duration, cash flow generating infrastructure projects. By disaggregating and reallocating risks (reflected in CAPM's beta), it creates a robust structure that:

Attracts diverse investors by clearly articulating risk-return profiles (optimized through WACC)

Optimizes leverage to enhance equity returns while managing risk

Provides a clear benchmark for ongoing project performance evaluation

Facilitates complex risk allocation strategies among participants

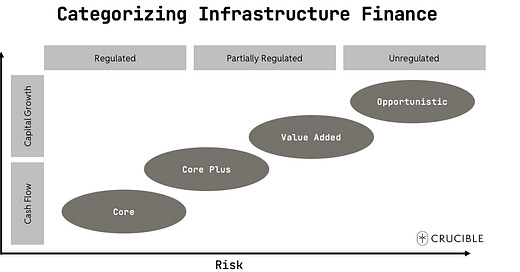

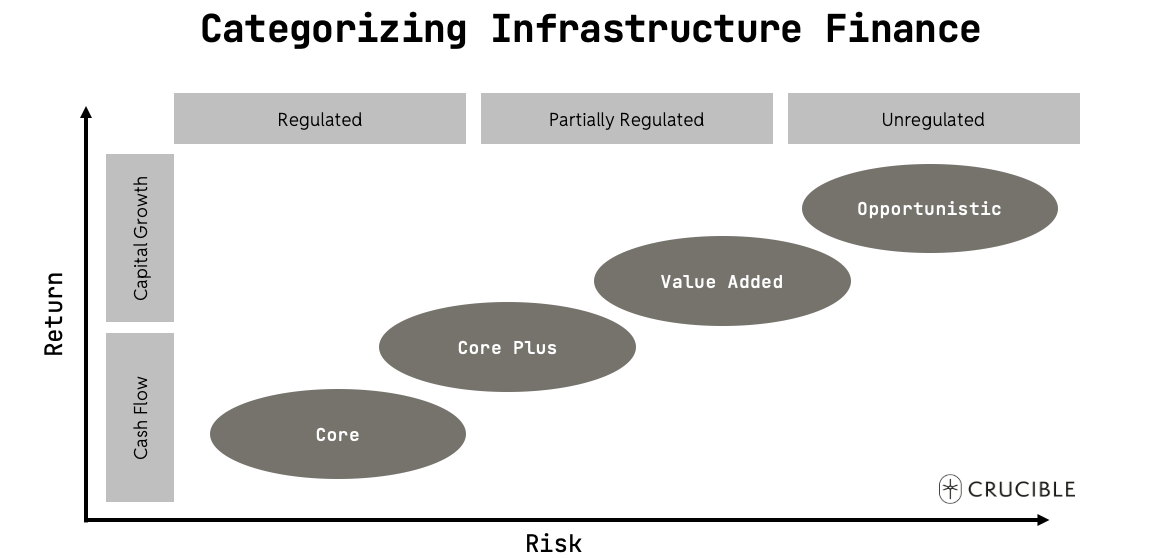

Like any other investment category, there are different types of infrastructure investments based on risk and return. DePIN today is more value added / opportunistic given the unregulated nature of many of these emergent ecosystems and the material capital appreciation potential of these networks and subsequently, their tokens.

As this new category of infrastructure finance through distributed networks incentivized with tokens and stablecoins emerges, we feel it is important to create a body of knowledge that is expressed in the language of finänce that makes this category accessible to traditional investment professionals and allocators seeking risk-adjusted returns driven by both cash flows and capital growth.

What the DePIN?

Now that you have completed an entry level course in project finance, let’s connect it to what’s happening in DePIN.

At Crucible, we firmly believe evolution of network states will include ambitious infrastructure projects in the physical world that are financed, owned, and funded by a wider group of stakeholders using tokens.

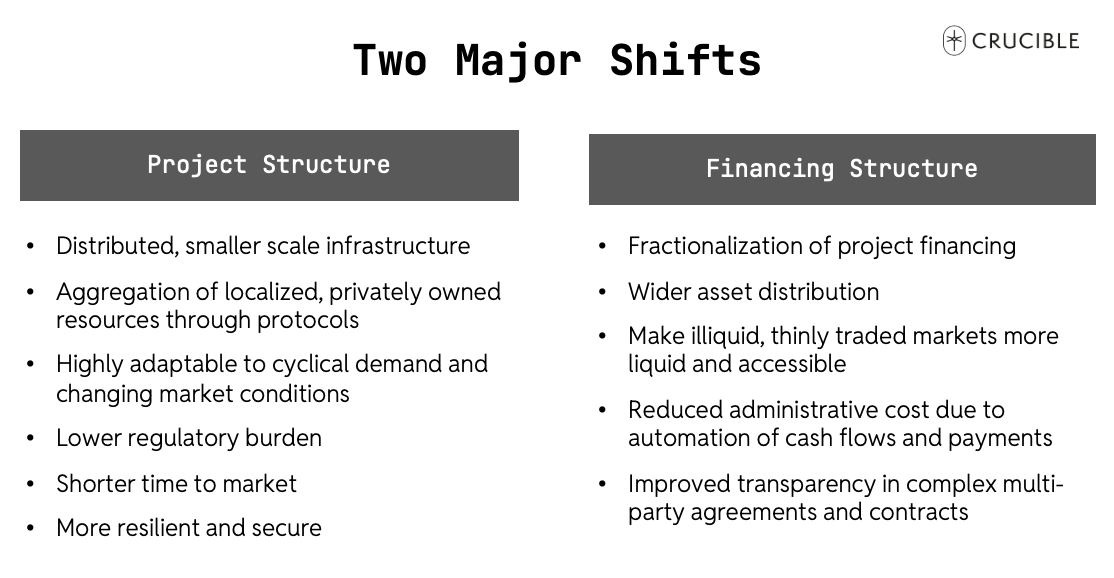

There are two keys trends driving the DePIN opportunity, and they pertain to project structuring and as a result, new options for financing. DePIN is still in its early days and as a result, we do not yet have best practices for how these projects should be structured and in turn, financed, in order to generate a sustainable model for DePIN network development and maintenance.

Challenges of Token Models in Supporting DePIN Growth

Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePIN) projects face significant hurdles in leveraging typical token models to support the capital expenditures required for growth. This misalignment stems from several interconnected factors inherent to both blockchain-based tokenomics and traditional infrastructure financing.

The Fundamental DePIN Disconnect

At the core of the problem lies a fundamental disconnect between the short-term, volatile nature of most token economies and the long-term, stable funding requirements of physical infrastructure projects. While DePIN token models often excel at incentivizing network participation and covering operational expenditures (OpEx), they struggle to provide the large, upfront capital injections necessary for infrastructure deployment.

Financial Modeling Challenges

When viewed through the lens of traditional financial metrics like CAPM and WACC, the challenges become more apparent:

High Risk Premium: The volatility and uncertainty of token values lead investors to demand a high risk premium. According to CAPM, this results in a higher required rate of return, increasing the cost of equity for DePIN projects.

Limited Access to Debt Financing: Traditional lenders are often hesitant to provide loans against crypto assets or tokens due to their volatility and regulatory uncertainty. This limits DePIN projects' ability to access cheaper debt financing, pushing their WACC higher as they rely more heavily on expensive equity capital.

Mismatch Between Token Volatility and CapEx Stability: While token values can fluctuate wildly in short periods, the costs associated with physical infrastructure are stable and denominated in fiat. This mismatch complicates long-term CapEx planning and execution. Additionally, token models encourage short-term speculation rather than long-term infrastructure investment, focusing on price appreciation instead of sustainable network growth supported by balanced economics that reward capital outlay appropriately.

Long-term Planning Difficulties: Uncertainty in token values makes it challenging to create accurate long-term financial projections. This can lead to higher discount rates in net present value (NPV) calculations, potentially making many CapEx projects appear less attractive or unfeasible.

Regulatory Uncertainty: The evolving regulatory landscape for tokens adds another layer of risk, further increasing the cost of capital for DePIN projects.

Lack of Asset Backing: Unlike traditional infrastructure financing where physical assets serve as collateral, tokens often represent abstract concepts of network participation or utility, making it difficult to secure typical infrastructure loans.

Inflationary Tokenomics: While effective for driving network growth and participation, inflationary tokenomics may not be well-suited for generating substantial upfront capital needed for infrastructure deployment.

Governance Challenges: The distributed decision-making processes characteristic of many DePIN projects may not align well with the more centralized control over capital allocation that traditional infrastructure investors typically seek.

Scalability Issues: As DePIN projects grow, they often encounter limitations in their token distribution models that struggle to support the massive CapEx requirements of widespread infrastructure deployment.

While token models have been instrumental in bootstrapping many blockchain projects, their inherent volatility and the unique CapEx requirements of DePIN projects create significant challenges. Addressing these issues will be crucial for the long-term success and growth of DePIN projects.

As the DePIN economy evolves, innovative approaches that bridge the gap between traditional infrastructure financing and blockchain-based tokenomics will be necessary. This might involve developing hybrid financing models, exploring more stable token designs, or creating novel structures that better align with the long-term nature of infrastructure development. By grounding project finance in fundamental corporate finance concepts, DePIN projects can create sophisticated, tailored financing structures that align the interests of various stakeholders while maximizing the probability of project success.

Stay Tuned for Part 2 where we explore alternative DePIN financing structures that draw from the CAPM model.

dflx.xyz have built a crypto funded infrastructure model you should check out

very informative write up !