Building a Datacenter Part II

Adopting 800V DC: The Future of Power Systems, Racks, Cooling, and Management Systems

Note: this report was modified from its original version. For the downloadable PDF report, including footnotes and additional graphics, please visit:

"I think Moore's Law will be dying within a decade." Gordon Moore, 2015

Intro: From the PC Revolution to Cloud Compute

It’s true, frontier models were not around when we were born, and it goes without saying that demand for compute has gone from 0 to 100 over the course of our lifetimes. As students of history, we find value in reflecting on the course of compute and how underlying systems have kept pace and evolved at a time when site infrastructure is at an inflection point, namely via the industry’s adoption of a high voltage direct current power system as ordained by Nvidia, which we’ll get to and discuss at length after this brief intro. Before that, if you care to join us, please sit back and enjoy a brief ramble on the history of compute, which we promise will eventually lead us into a detailed dissection of cutting edge datacenter power and cooling systems. But first, let us indulge.

From 1990 to 2000, compute adoption was PC adoption and PC adoption was compute adoption, thanks to the dawn of the IBM personal computer in 1981 which arrived off the heels of the introduction of microprocessors in the 1970s. Total global FLOPs in the 90s are estimated to have been in the low petaFLOPs (10-50 million MFLOPs) vs. today’s capacity of 1-10 trillion TFLOPs.1

Does this look familiar? We were budding millennials at the time, but we’re told these 80s era devices could be used to write book reports, access dial up internet to share files, and even play dice games. The first digital businesses emerged in the early 80s, with Boston Computer Exchange’s (BoCoEx) seminal launch in 1982, predating the 1991 public introduction of the World Wide Web and the 1995 launches of Amazon and Ebay.

Personal computers became all the rage with the rise of Windows user interfaces 95 and 98, falling unit prices, and the continued rise of the internet and online commerce. Amazon.com, a growing online retailer, had built up its own IT infrastructure for its online marketplace that it figured it could sell externally to other retailers - which brings us to the 2000s and the dawn of cloud services marked by AWS’s 2006 launch. Google’s GCP and Microsoft’s Azure would follow in coming years. The cloud era laid the groundwork for what would become a cornerstone of today’s compute market: global datacenter capacity grew steadily from 24 GW in 2006, focused on basic Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), to roughly double that figure in 2022 - primarily on cloud services expansion - before November 2022’s launch of Chat-GPT, after which compute supply and demand growth reached another level of escape velocity.2 Goldman Sachs estimate 2025 datacenter capacity to be 70 GW in the US alone and forecast 122-146 GW of demand by 2030. 3

Side Bar: The Boston Computer Exchange & Compute Markets

The Boston Computer Exchange (often abbreviated as BCE or BoCoEx) was founded in 1982 as the world's first e-commerce company. It operated as an online marketplace for buying, selling, and trading used computers, initially using a bulletin board system with a database accessible via platforms like Delphi, YellowData, and later CompuServe's Electronic Mall well before the public internet era. Sellers uploaded inventory, buyers browsed listings, and transactions were finalized by phone. BCE took a commission - a simple business - and added escrow services to handle disputes. They created the BoCoEx Index, a weekly price report for computer models that became a standard reference in publications like Computerworld and PCWeek, and an automated auction system demonstrated at COMDEX in 1986. At its peak, BCE licensed its technology to about 150 affiliated "Computer Exchanges" worldwide, including in the US, Chile, Sweden, and Russia. After eight years, the company sold to ValCom, a computer retailer that redirected its focus toward liquidating excess inventory. It was later acquired by Compaq Corporation which itself was acquired by Hewlett-Packard after which BCE ceased operations and was shut down.

We love studying the formation of new markets having built, traded, and invested in various new markets from commodities to crypto and find this case study seminal in light of the resurgence of multiple new forms of GPU marketplaces today.

Crucible are investors in OrnnCx, a compute derivatives desk who manage bespoke contracts for all risk vectors within the GPU value chain, and Compute Index, a venue that facilitates term and on demand GPU hour transactions.

Fluidstack, now one of the fast growing neoclouds in the world, originated as a UK based peer-to-peer GPU hour marketplace in 2022 and expanded to cloud deployments upon the launch of ChatGPT. The San Francisco Compute Company arose as one of the first San Francisco based GPU hour spot marketplaces serving AI start ups in recent years. Andromeda began as a vehicle to provide compute to NDFG portfolio companies and is now a bellwether in GPU services for start ups. There’s a lot of activity in this space now, we are excited about the opportunity to optimize financial flows in the compute economy, including things like stablecoin payment flows, billing automation, and settlement financing, which Internet Backyard are seeking to solve.

Waves of Exponential Demand

An exponential growth in token consumption translates directly into demand for parallel GPU clusters for both training and inference. As a result, data centers have moved from tens of megawatts of load in the early 2010s to tens of gigawatts by the mid‑2020s.

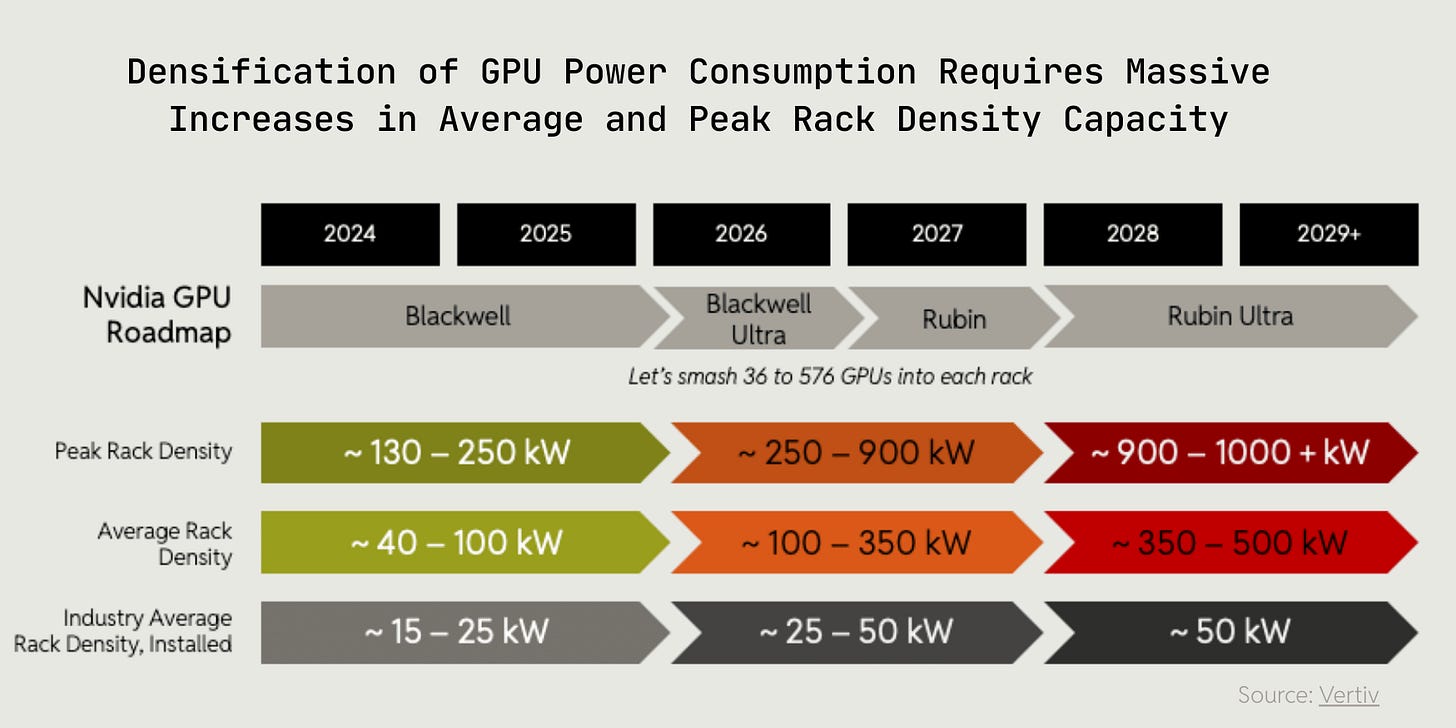

Each GPU generation delivers higher performance but also increases peak power draw per device, with modern AI accelerators moving from tens of kW to hundreds and soon 1k+ kW per rack. In dense AI racks, configurations of eight high‑power GPUs per server and multiple servers per rack routinely push power demands to hundreds of kW per rack, far above traditional data center designs. This rising power density forces adoption of advanced cooling such as liquid direct to chip systems to manage the additional heat, adding further indirect energy overhead. The racks are melting every time you talk with your AI waifu girlfriend. You better marry her and solve our population decline problem or Elon will shadow ban you forever.

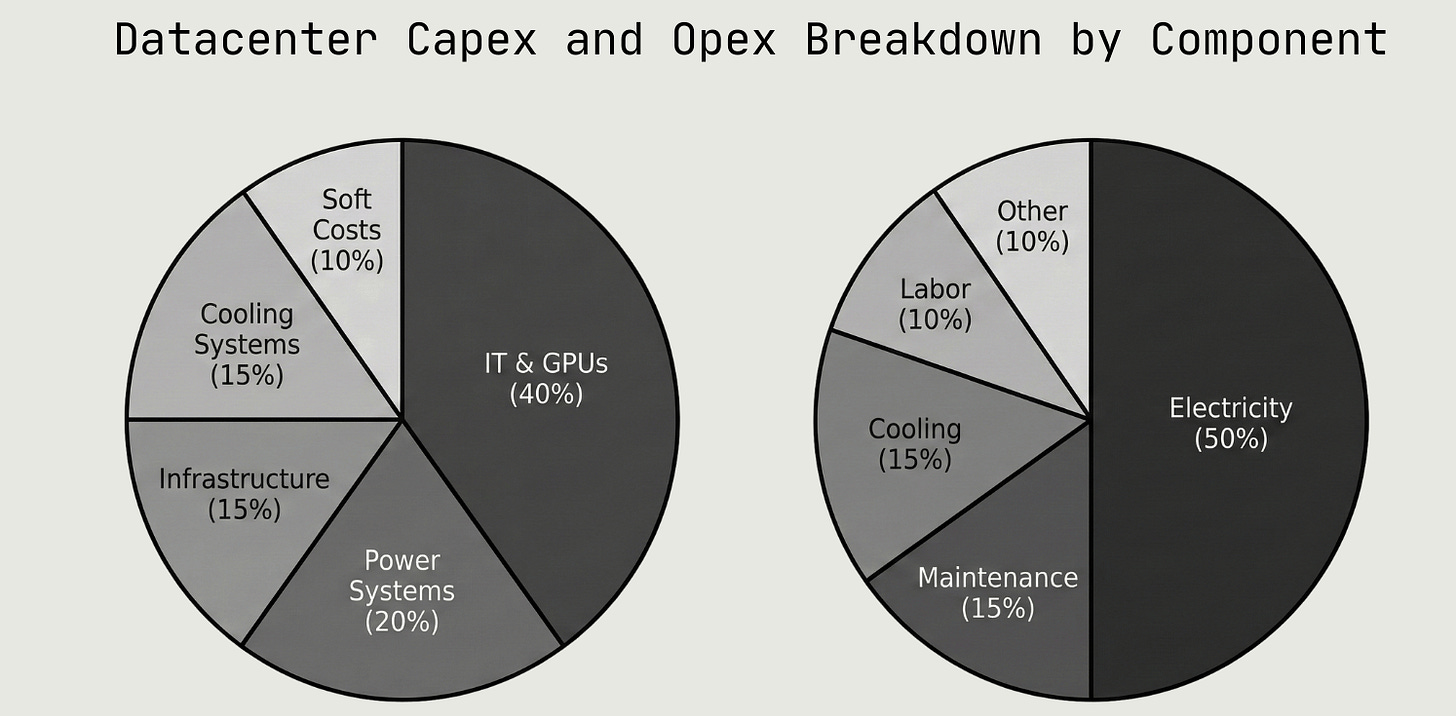

As demand for virtual compute via waifus and LLMs pushes the physical world to adapt to efficiently produce FLOPs, it’s helpful to contextualize the $ spend attribution of physical compute systems. Illustrated above, power and cooling systems comprise ~35% of capex spend and an even greater share (the majority) of datacenter operational expenditure.

At the macro level projections now suggest that AI‑driven data centers could claim a double digit share of new generation capacity in the coming years (good thing we are also going to space), underscoring how AI compute growth is tightly coupled to a steep, system wide rise in power consumption. Note that it isn’t simply a “more power” problem. That is naive, and frankly, makes you look stupid. It is a more power and better power systems and better heat management problem. So please do not tell us about how SMRs or solar will solve all of the power problems facing data centers. Instead, continue reading and be slightly less stupid, if you please.

As lovers of complex systems and investors in companies that enable them, we find value in understanding and dissecting the minutia of the evolution in compute architecture that makes this growth possible at all.

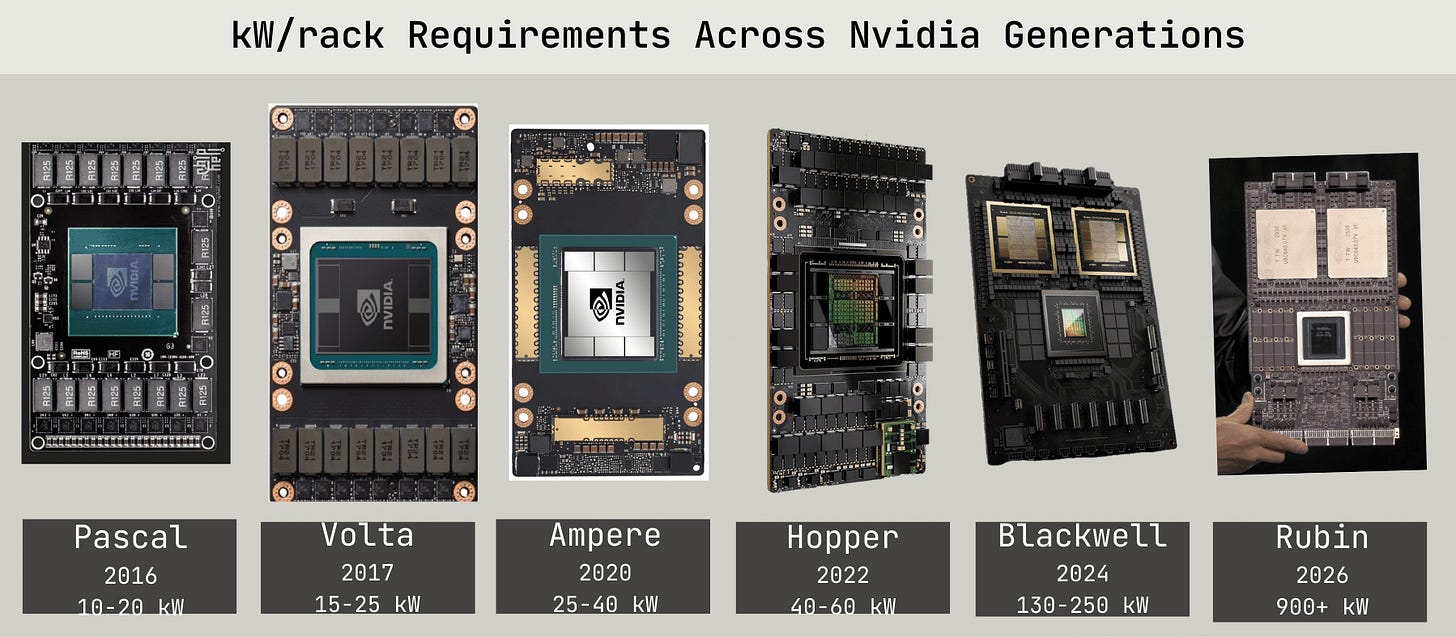

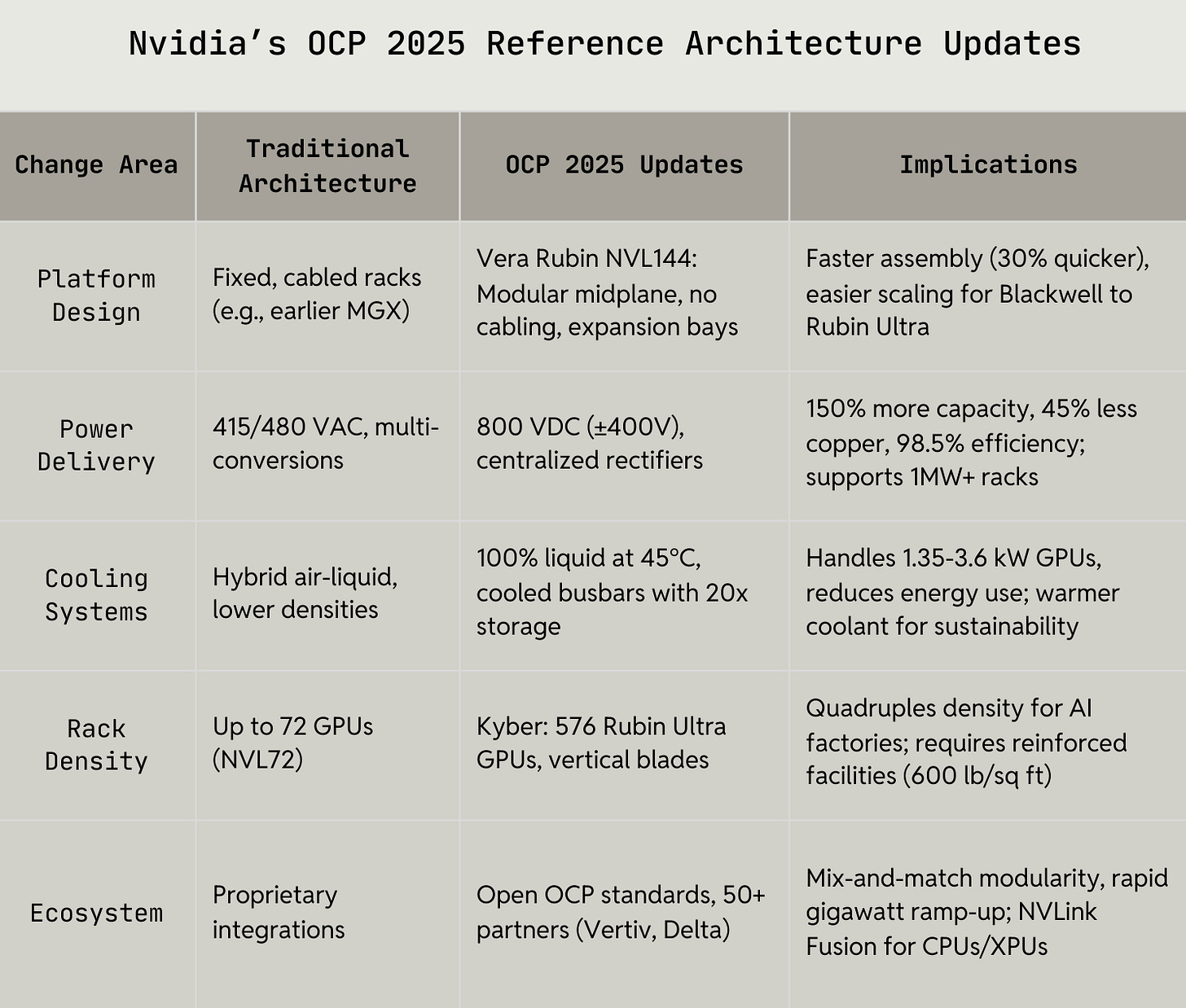

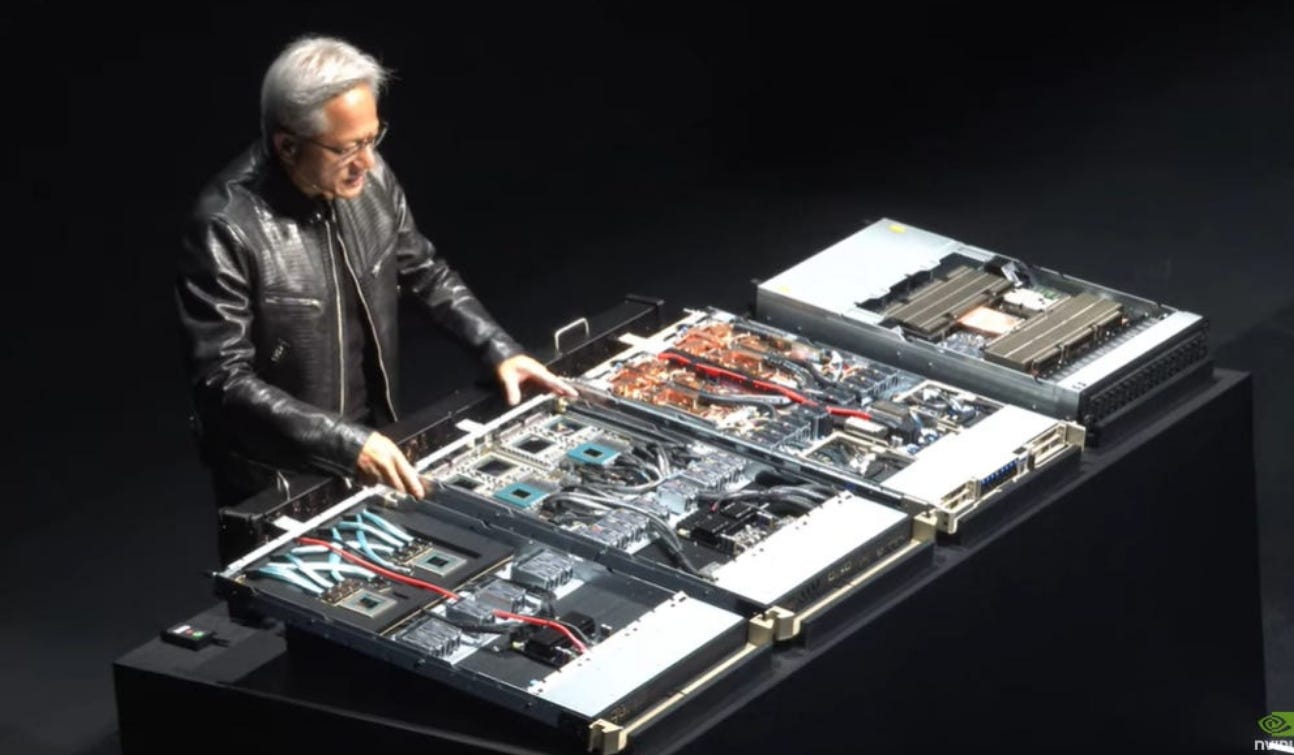

The progression of Nvidia’s reference architecture is a good heuristic to study as the company’s designs represent the de facto standard for power & cooling systems and compute rack design. And no, we aren’t just saying this because Nvidia is the largest company in the world and is decidedly cleaning up on margins vs. the rest of the datacenter value chain to date.

More importantly, Nvidia’s leadership in setting the output and the kW per rack consumption of modern compute systems has pushed site developers and manufacturers at large to adapt to meet the company’s increasingly onerous power demands. Despite recent competition from AMD and Google on their respective GPU and TPU performance, the market still follows Nvidia’s lead in adopting higher critical IT requirements with each Nvidia generation, high density liquid cooling, and recently, a shift to high voltage direct current (DC) power systems, which has reverberating effects on multiple parts of the datacenter.

Put differently, Nvidia jumps and every other manufacturer says “how high” to either serve or compete. See the power progression across the last six generations of GPUs.

Why are we showing you this? As new generations NVIDIA chips continue to push the boundaries of physics (every model is named after a physicist for a reason), they also push the boundaries of how much power and heat can be safely managed in the racks where GPUs are installed. Thermodynamics baby! We have some sexy pictures of stacked racks later on... we hope that is a sufficiently compelling carrot to encourage you to march on.

Rack Rack City: A Note on Thermal Density

Rack power density is decidedly the antagonist driving all other datacenter systems forward, because the electrical and cooling systems that feed each rack cannot scale as fast as GPU power draw of each next gen chip. Let me bend your ear on the thermodynamics of dense computing clusters...

Computing is an exothermic process - the primary physical output is heat, the digital / virtualized output is FLOPs. GPU racks convert almost all of the consumed electrical power into heat and traditional air‑cooled designs (think fans on your home PC - throwback for our fellow nerds who built gaming PCs to flex on other nerds at LAN parties) hit practical limits around 15–20 kW per rack. While liquid cooling can support more power draw, per rack heat limits require operators to leave space or spread GPUs across more racks, which constrains overall cluster scale and adds cost, and introduces constraints on physical networking meshes (we will cover those in Part 3) that link GPUs across clusters together into consolidated resource pools. Physics rule everything around me, especially in compute.

There’s also a security hazard - supplying 100 kW or more to a single rack requires multiple high capacity circuits or higher voltage distribution, increasing complexity, cost, and fault risk at the rack and row level. As AI designs push toward even hundreds of kW per rack (see prior page, a single Rubin rack will draw 900 kW), the rack becomes limited by what the site’s power and cooling backbone can safely deliver, making rack density, not silicon performance, the hard ceiling on how far AI data centers can scale at a powered site.

As the chart above illustrates, as racks get stacked with GPUs slated to require 1,000 kW (that’s 1 MW kek) of density, rack design and materials need some upgrading. Rack power density is forcing racks to become structurally stronger, thermally integrated, with different materials, geometries, and mounting features to dissipate and manage such intense power density. In rack city we throwin’ hundreds, hundreds (of kW of power).

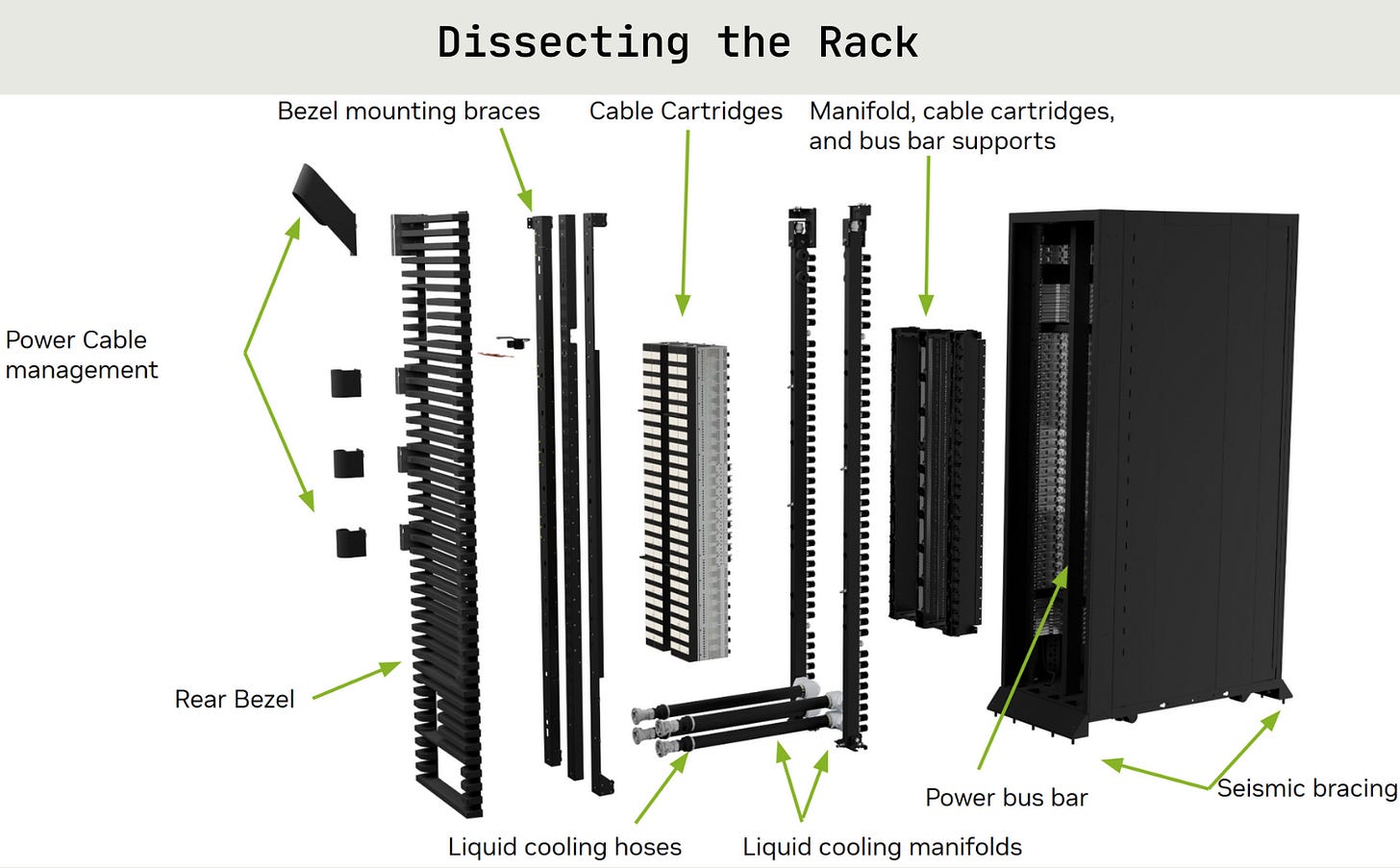

Check Out Our Rack: A Visual Guide

We’re going to be talking about racks a lot so let’s give you some of the high level terminology and a good visual. The rack itself is a big, heavy metal box with a bunch of components in it to accommodate all the various pieces that go in - GPUs, CPUs, storage drives, networking gear, power systems, cooling systems, and more. The heat density of new racks requires the use (expensive) steel that can hold up to high temperatures.

Once the rack is bolted to the floor with seismic bracing, the internals can be installed, usually in pre-built trays that slide in, and then all of the power cables, liquid cooling piping, ethernet cables, and more get plugged in. and then you hope it doesn’t melt, flood, or blow up. SICK.

OCP: Codifying Hardware Standards (and Moats)

Now you know racks. Lets add on. Most people think of Nvidia as a company that makes GPUs. In reality, Nvidia is building a tightly coupled hardware and software design ecosystem which is reinforced through its contributions to the Open Compute Project (hereforth referred to as OCP) as the catalyst to turn its GPU “AI factory” designs into open reference standards for racks, power, cooling, and networking, so operators can build interoperable, repeatable data center architectures instead of bespoke one offs.

Nvidia (and other OEMs) use OCP to codify data center architecture via their own standard reference implementation. The entire compute value chain - co-los hosting compute, OEMs making parts, and hyperscalers building their own vertically integrated operations - can follow the playbook rather than re‑invent the wheel. OEMs like Vertiv and SuperMicro follow Nvidia’s lead and then build compliant power, cooling, and rack ecosystems that further codify these standards across the industry. The evolution of datacenter systems is a spectacle of coordination between these behemoths.

Using an OEM, like Nvidia’s, reference architecture streamlines deployment because you inherit validated rack, power, networking and cooling blueprints etc. (which many compute customers are used to). It also improves supply chain flexibility and resale or repurpose, since multiple manufacturers target the same open specs rather than a closed, vendor‑specific architecture (EXCUSE ME, I HAVE A COMPLICATED ORDER).

Cleverly, the concept of reference architecture also further reinforces Nvidia’s entrenchment as the Arrakis of compute, ensuring its control over spice production. There are profound positive *and* negative externalities that result from the standardization that must be weighed carefully as the shift towards more heterogeneous standards is being promoted by other chip makers vying for Nvidia’s crown. Is Nvidia House Harkonnen or House Atreides? We will leave it to you to decide. (We lean Atreides, Jensen you are our Duke Leto.)

The End of the Beginning

If you’ve made it this far, we salute your bravery. That was just the warm up. In this second report on “How to Build a Datacenter,” we explore the complex, layered regime shifts in datacenter power and cooling systems and contextualize where we see room for investment or have already placed our chips as early stage investors, avid traders, shrewd lenders, and owners and operators of a growing Nvidia B300 HGX cluster.

Note our first report covered the datacenter tiering system - for the purposes of power systems and redundancy we’ll assume a Tier 3 site in this report, as this is the most common for large facilities globally. We will do our best to simplify what seems complicated at face to a “for dummies” level (we can’t include that in the title anymore because we were scolded for copyright infringement following Part I). After all, we are dummies, especially us, which is why we write these reports.

Given the gravity of the shift, we focus most here on Nvidia’s announced shift to 800V direct current power systems in forthcoming reference architecture and the second order implications:

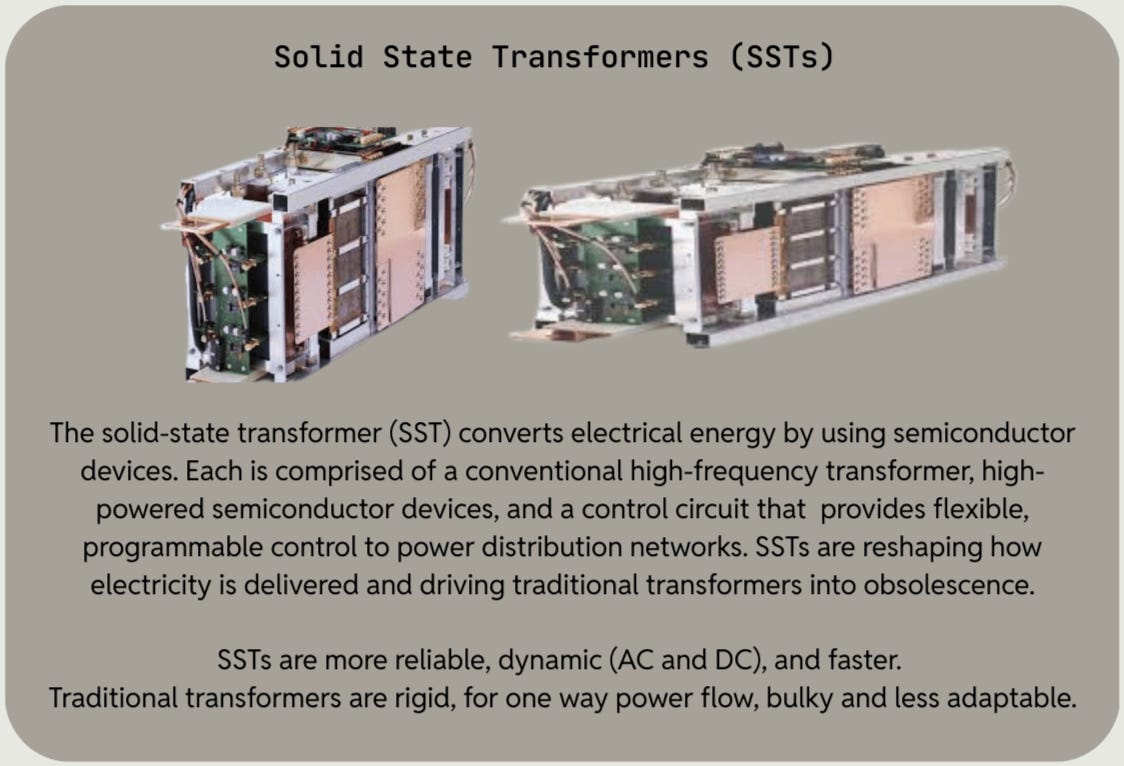

new transformers (solid state transformers)

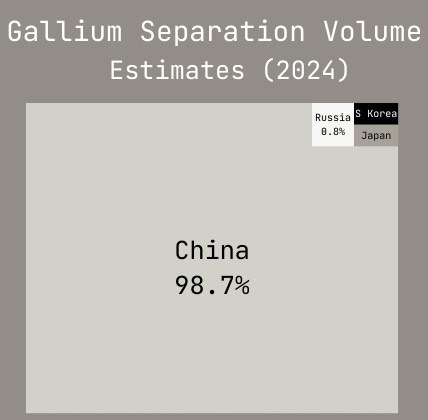

new materials (gallium anyone?)

supercapacitator and BESS systems alongside the traditional UPS system

streamlined (finally?) liquid cooling systems, and;

how to monitor and maintain increasingly dense racks

Without further ado, join us on this wild ride. Yeehaw.

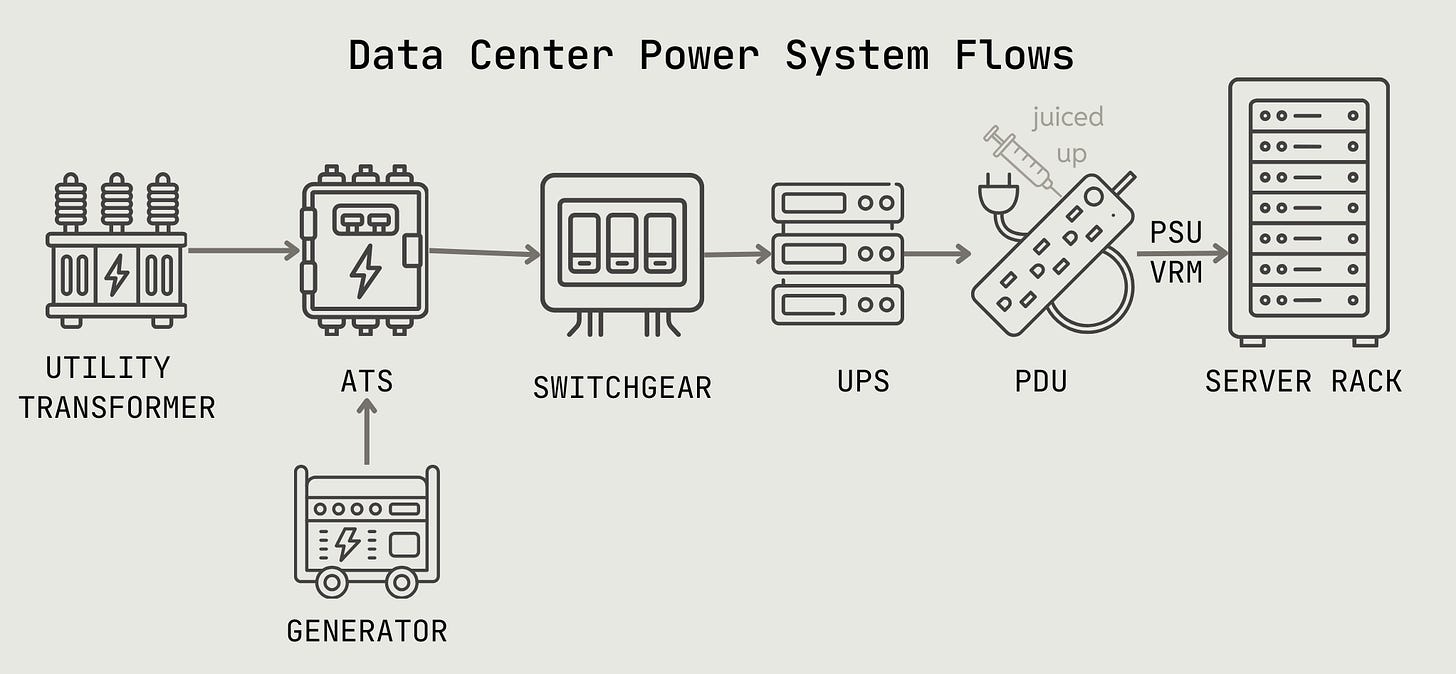

Power Systems and the Dawn of the 800V DC Era

First, let us walk through a datacenter power system. The server in this diagram is another name for the rack that holds the GPUs. Everything else outside of that comprises the power system needed to feed electrons to the server rack.

Let’s take each component of the power system from the top:

A utility company delivers high voltage power and a transformer steps down the voltage from high to medium voltage for the site to consume. Hyperscale size sites typically reside near high voltage transmission lines so on-site substations (containing transformer, switchgear and other equipment) are required and either self-built or sourced via the utility. Depending on size and voltage class, substations cost $500k to $50M.

The switchgear transfers medium voltage power to a second transformer adjacent to the data hall (i.e. the room full of server racks) to step down from medium to low voltage.

Alongside the transformer is a back up generator (diesel, baby) that the site taps into in case of a power outage, in which case the Auto Transfer Switch (ATS) switches the power.

From here, power distributes along dual paths:

Toward the cooling equipment (more on this later)

Toward the racks, as follows:

Power flows through a UPS (uninterruptible power supply) system - basically a back up system of 5 to 10 minute battery storage that kicks in instantly during power outages or fluctuations until the generator comes online.

Through the UPS, the power is supplied directly to the server racks via Power Distribution Units (PDUs) which is a fancy way of saying power strip on steroids, or growth hormones, or Chinese peptides. Make America strong again!

At long last, electricity from the PDU is delivered to the chip via power supply units (PSU) - a converter box that converts AC (alternating current) electricity into stable DC (direct current) - and voltage regulator modules (VRM) - a precision valve that fine tunes and stabilizes the voltage to feed CPUs and GPUs.

HOLY ACRONYMS. GOD BLESS DATA CENTER ENGINEERS.

With the foundation of how power flows from the grid to the chip established, let us address Nvidia’s proposed shift to direct current power systems inside the datacenter and what this means. First we’ll define the two distinct power systems and their history to understand their tradeoffs and how we arrived at the breaking point of AC systems.

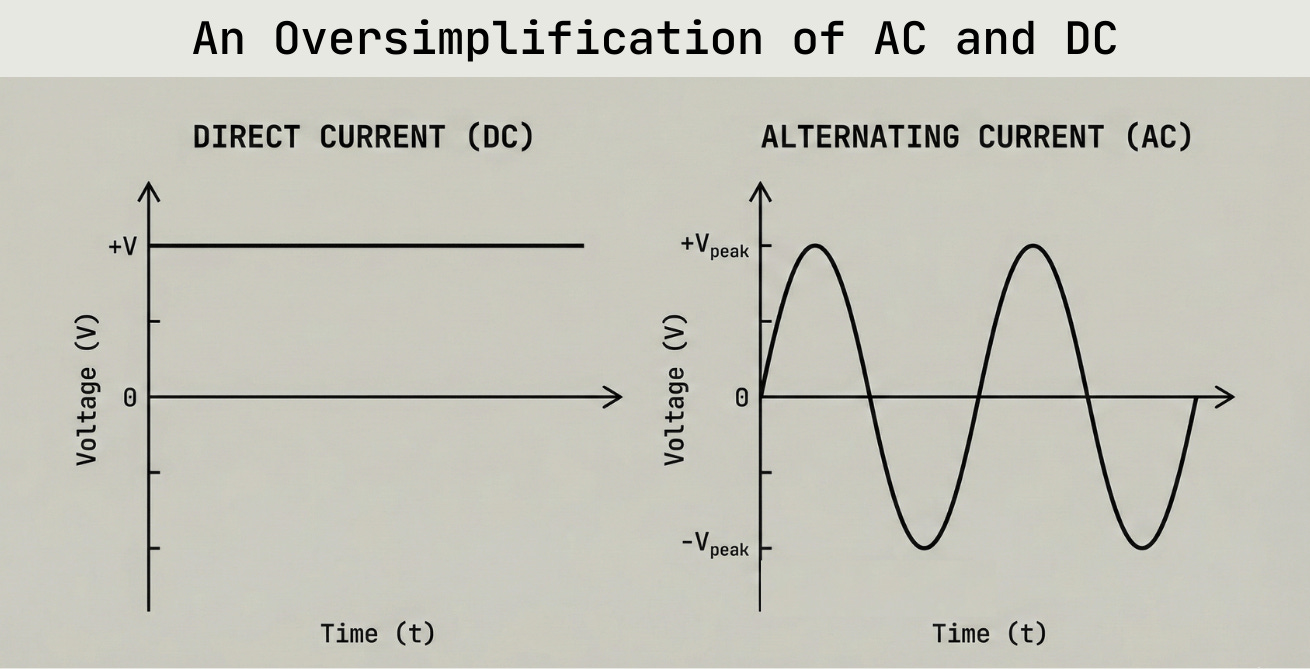

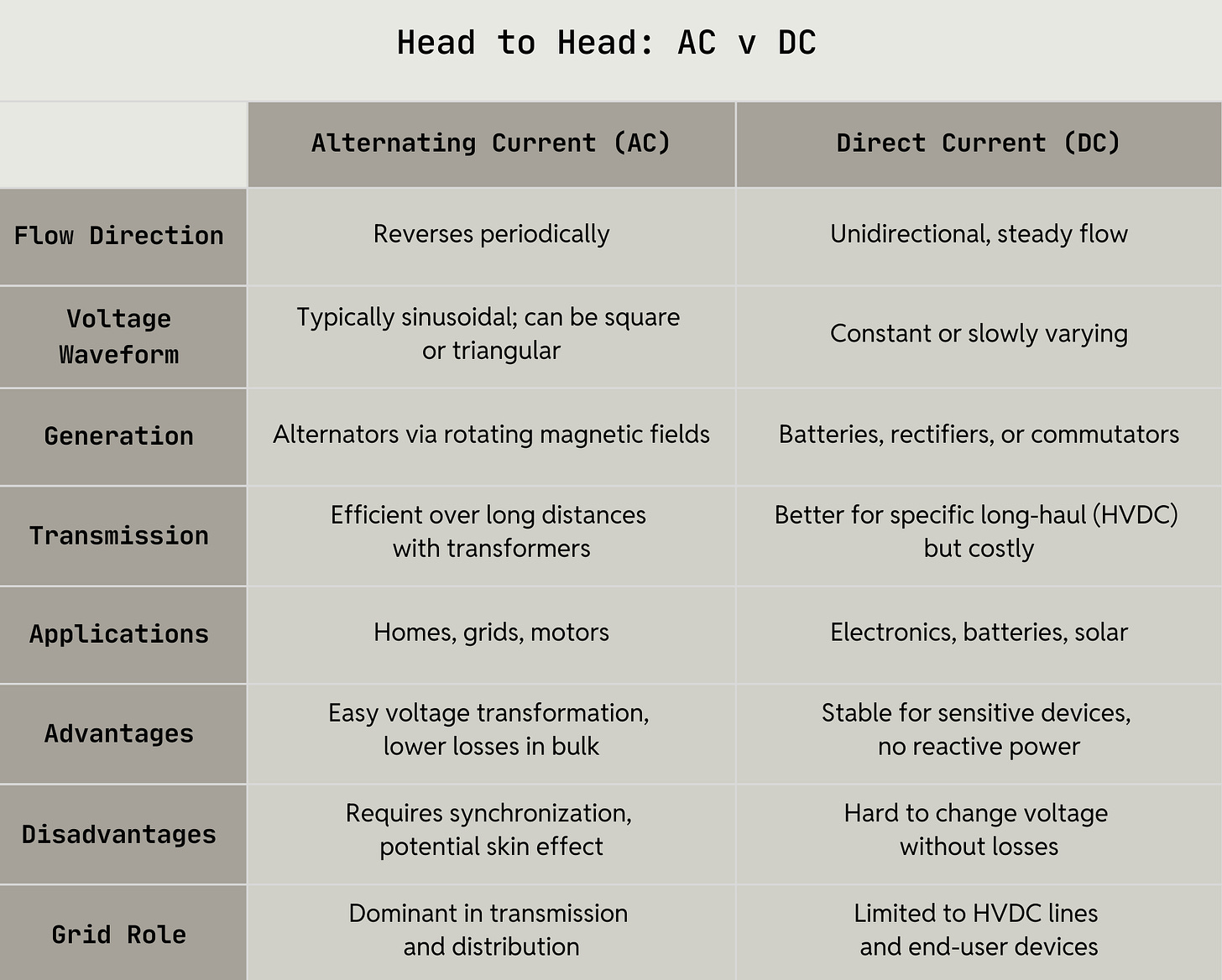

Alternating Current (AC): electric charge periodically reverses direction, commonly used for powering homes and grids due to efficient long-distance transmission. Team Tesla and Westinghouse.

Direct Current (DC): electric charge flowing in a single, constant direction, typically found in batteries and electronics for stable, unidirectional power delivery. Team Edison.

Modern electrical grids are primarily AC based, allowing for voltage transformation and reduced energy losses over distances (travel at high voltage then transform to lower voltage for consumption), though some specialized high voltage lines use DC. The AC system drives the requirement for the specific transformers discussed above - to step up voltage for transmission and step down for consumption multiple times.

The lore behind the adoption of AC dates to the late 19th century War of the Currents, a rivalry between Thomas Edison (DC proponent) and Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse (AC proponents). Edison, holding DC patents, built early power stations but faced limitations: DC required local generation every few miles due to slower transmission than AC at the time. He campaigned against AC, claiming it was dangerous, going as far as publicly electrocuting animals to demonstrate risks.

Tesla’s AC system, with inherent transformable voltages, allowed high-voltage transmission with low losses, revolutionizing distribution. AC took victory starting at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair where Westinghouse’s AC bid undercut Edison’s DC and again in 1896 when the Niagara Falls project used Tesla’s AC to transmit power 26 miles to Buffalo, proving scalability. By the early 20th century, AC became the standard, enabling widespread electrification - though HVDC is used for specific cases like undersea cables or interconnecting unsynchronized grids, as it avoids synchronization issues and reduces losses over extreme distances.

So, why the shift to DC within the datacenter now?

Post the Current Wars, AC served the foundation of datacenter power systems since their inception in the 1960s given AC aligned with global electrical grids established in the 1800s as just discussed. Early datacenters relied on 415V or 480V three-phase AC for its ease of distribution: voltage could be stepped down within the building for equipment and it supported standard uninterruptible power supplies and cooling systems. As datacenters evolved through the 1990s internet boom and 2000s cloud era, AC remained dominant, handling rack densities of 5-20kW with relative ease.

While AC excelled in transmission during this time period, limitations became more evident as power demands increased. Modern servers, GPUs, and storage devices inherently operate on DC, necessitating repeated conversions within the power flow: AC from the grid is rectified to DC for UPS batteries, inverted back to AC for facility distribution, and rectified again to DC at the rack or server level. Each step incurs losses, amounting to typical levels of 10-20% power leakage.4 That is non-trivial!!!

Given the inefficiencies are exacerbated as rack density increases, DC started to become more interesting in the 2000s with datacenter energy consumption rising to 1-2% of global electricity upon the proliferation of cloud computing.5 First efforts like the Open Compute Project in 2011 introduced 380V-400V DC systems to streamline power delivery, reducing conversions to a single grid-to-DC step and improving efficiency by 5-10%.6

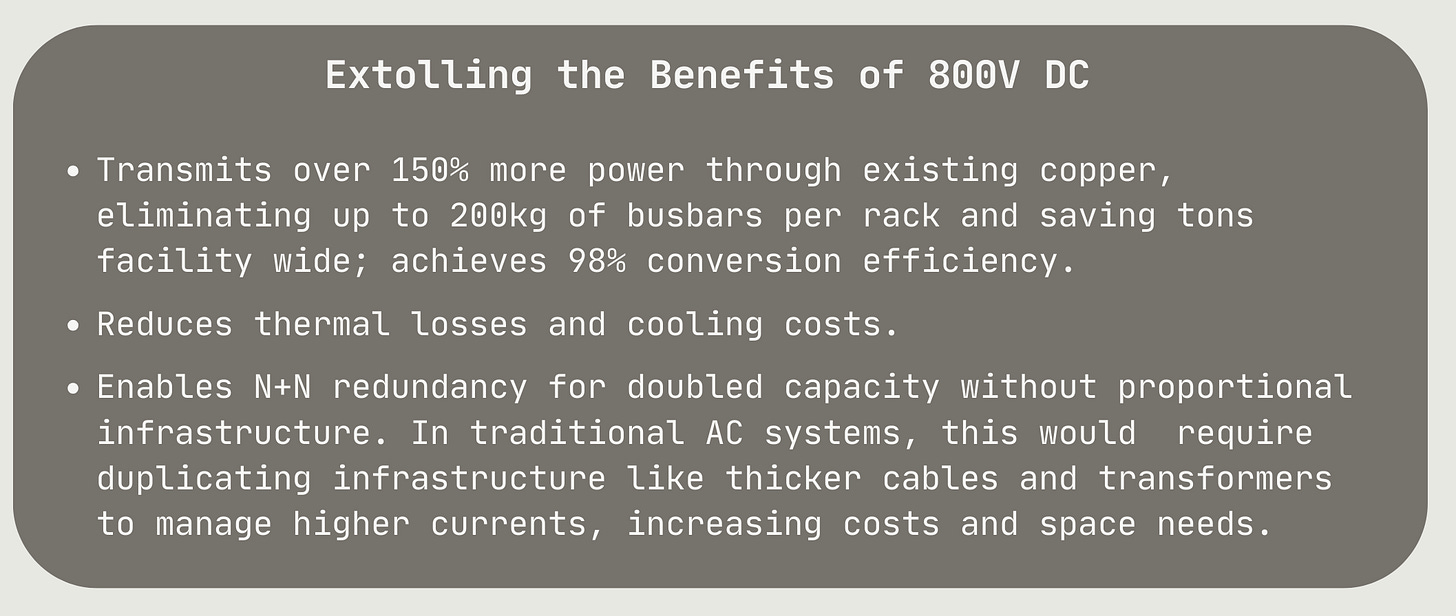

As discussed in the intro, with Nvidia’s newest Blackwell and Rubin systems commanding 1.35kW per GPU and up to 3.6kW per GPU respectively, power requirements are multiplying from 10-20kW to 100kW-1MW+ per rack, further straining AC systems with high currents that demand thick copper busbars (up to 200kg per rack) and exacerbate power losses. Put bluntly, the inefficiencies of AC in meeting increasing rack density demands are now unmanageable.

Nvidia’s plan to address this in forthcoming infrastructure is to adopt 800V DC power systems, built on lower voltage DC foundations but targeted to extreme densities. Nvidia took inspiration for this from adjacent fields: electric vehicles adopted 800V batteries for faster charging and reduced wiring weight, while solar and long-distance HVDC (since the 1950s) used high voltages for minimal losses over distances. NVIDIA’s 2025 announcement at the OCP Summit formalized 800V for Vera Rubin’s architecture, supporting Blackwell and future Rubin and Rubin Ultra GPUs. In practice, grid AC will be converted once to 800V DC at the perimeter of the datacenter via rectifiers, distributed through efficient busways, and stepped down at racks to 54V/12V DC for consumption.

Reconfiguring for 800V DC

To achieve these benefits, numerous parts of the datacenter need to be reconfigured for the datacenter to centralize high voltage rectification at the facility perimeter, distribute 800V DC via busways to rows, and perform local DC-DC step-downs at racks.

Skip the Stepdowns: Solid State Transformers

Innovation is everywhere! Solid state transformers (SSTs) replace conventional magnetic core transformers with power electronics for intelligent, compact voltage management. Unlike traditional transformers, which are passive devices using electromagnetic induction for AC voltage stepping, SSTs use high frequency switching via silicon carbide (SiC) or gallium nitride (GaN) transistors, enabling bidirectional power flow, voltage regulation, and fault isolation in a fraction of the size (30-50% smaller footprint) and weight. As of December 2025, SSTs are advancing toward production readiness for datacenters: the global market is valued at $115M in 2025 after early pilots in EVs and renewables and projected to reach $375M by 2033 at a 16% CAGR.7

The SST collapses several of the steps in traditional power conversion into one coordinated, digitally controlled power conversion stack to reduce power loss. SSTs deliver DC directly for balanced distribution, enabling 150% more power flow through existing conductors which eliminates the need for bulky copper busbars (up to 200 kg in copper savings per rack), which Nvidia specifically cites as impractical. Another benefit - SSTs enable bidirectional power flow, moving power from grid to load or from distributed generation or storage back to the grid, making SSTs optimal grid‑level optimization and DER coordination.

Amperesand and SolarEdge / Infineon have launched collaborations for high efficiency SSTs tailored to 800V AI infrastructure, with prototypes demonstrating scalability to MW levels. More to come as these products are in their pilot phase now.

Sidebar: Critical Minerals so Hot Right Now

A critical mineral, Gallium, is the new “it girl” in industrials, playing a critical role in high-performance electronics. As we continue to push the physical limitations of silicon based chips,8 gallium based materials enable faster, more efficient and durable chips and power infrastructure. Gallium shows up in two different places in the datacenter: as a semiconductor material alongside silicon, and as an additive or liquid metal in niche interconnects where it can improve reliability or flexibility. Gallium isn’t found in nature as a free element - it’s recovered as a byproduct during the processing of other ores. As of 2024, nearly all gallium separation takes place in China via highly toxic processes.9

The charts above mirrors the breakdown of nuclear fuel conversion, enrichment and fabrication that we discussed in our 2025 nuclear fuel report - where US foreign adversaries control critical processes require to produce increasingly essential materials. This is not new information to our readers as China has persistently weaponized critical material access to the US throughout the 2025 trade war. We invested in Supra to provide an onshore, American alternative.

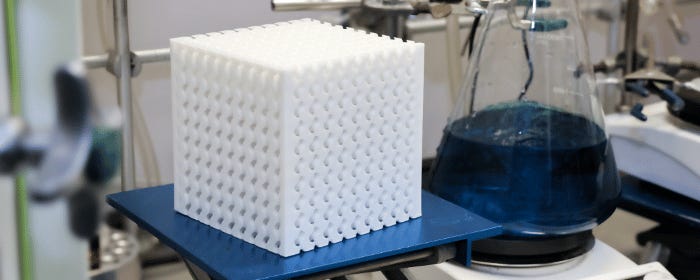

Supra is building proprietary technology to recover and monetize rare elements starting with gallium (and scandium) from mining streams by making previously uneconomic recovery commercially viable. Existing methods like solvent extraction (sx) and ion exchange (ix) often fail to reach high purity, struggle to separate different minerals, and come with high capex, high opex, and environmental downsides.

Supra solves this by embedding ion-specific supramolecular receptors into porous polymers. This approach blends the strengths of both methods while removing their weaknesses, creating an affordable, efficient, and flexible way to refine critical minerals. Their refining process has a small footprint, making it modular and easy to deploy, and ideal for processing highly concentrated rare earth tailings that cannot be easily separated, representing a potential multibillion dollar opportunity to build the largest strategic reserve of critical minerals in the Western hemisphere from mining waste.

Energy Storage: Supercapacitators and BESS

Back to the necessary changes to meet 800V DC datacenters, and onto energy storage:

The upgraded power delivery regime commands a new energy storage system with it. Traditional UPS in current datacenters are typically based on valve regulated lead acid (VRLA) batteries and provide reliable short term backup power (for 5-15 minutes) during outages, but they are ill-suited for AI’s dynamic power profiles. For example, model training can cause spikes up to 3x nominal draw in a single millisecond - UPS fall short in meeting these demands as they suffer from slow response times (10-20ms) and limited life cycle (200-500 cycles). To meet these demands, enter supercapacitors (we love this name) and BESS.

Supercapacitors discharge in microseconds to milliseconds, smoothing sub-second fluctuations without chemical reactions (vs VRLA batteries, which depend on chemical reactions that introduce delays and degradation over time). This allows supercapacitors to offer high power density (up to 10kW/kg) and near infinite cycles (>1 million).10 This is vital for today’s new Blackwell systems and beyond, which demand stable voltage amid 1.35kW+ draws per GPU. Supercapacitators are made by SuperMicro, Eaton, Delta Electronics, and Analog Devices - demonstrations took place at OCP 2025. Cost: $2,500-$10,000 per kWh (high due to short-duration focus) versus traditional UPS at $271-$500 per kWh, but offering lower total ownership costs through durability.

For longer ramps (seconds to hours), BESS, typically lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) systems, are deployed as a compliment, providing more scalable storage (MWh-scale) with 95%+ round-trip efficiency and 6,000+ cycles.11 BESS enables peak shaving (reducing grid draw during surges, a potential cost cutting mechanism in itself), demand response (participating in utility programs for revenue), and renewable integration (storing solar/wind output natively in DC). BESS are produced by Mitsubishi Electric Power Products (MEPPI), Capstone Green Energy with Microgrids 4 AI, and Honeywell with LS ELECTRIC. Cost: $75-$300 per kWh for cells, potentially 20-30% cheaper in lifecycle versus UPS due to scalability and efficiency.

The economics of adding supercapacitors into the storage stack are brutal: For 1MW, 15-second backup, supercaps cost 10-50x more per kWh than lithium-ion batteries.12 Notably, they’re not a UPS replacement - they’re an expensive addition to the power stack. So why deploy supercapacitors? They solve problems batteries can’t:

Clean incoming power and filter quality issues

Shape datacenter load and smooth power profile - GPU workloads create massive millisecond-level spikes

Mitigate utility demand charges (potentially millions annually at scale)

Help negotiate favorable utility terms - smooth load profiles make expansion approvals easier

This is added cost and complexity, but it’s the cost of doing business at 1.1MW rack densities where power quality and utility relationships become critical constraints.

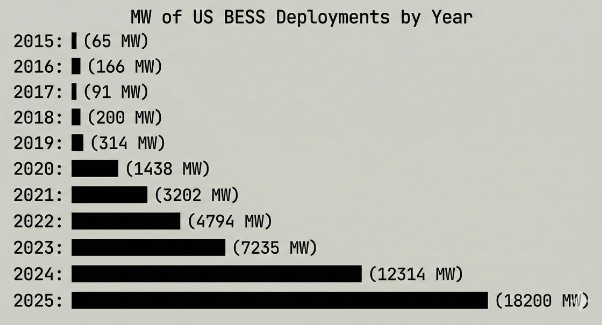

A Quick Note on Storage, Atta Girl BESS

Battery energy storage systems, or colloquially BESS, are the fastest way to add grid capacity. The EIA projects 18 GW of battery storage was installed in 2025 (a record), highlighting batteries as the quickest to build and integrate into the grid compared to solar (months to years) or fossil fuels (years).

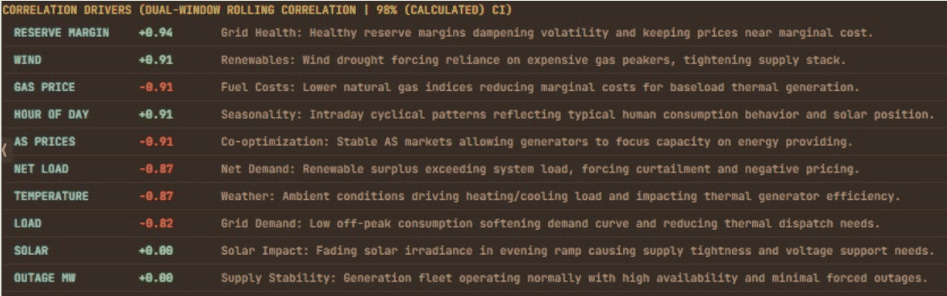

Shatterdome is a front-of-the-meter, trading centric network optimization for batteries, focused on maximizing arbitrage revenue. Clients achieve significantly higher returns vs. current Texas arbitrage levels, aiming for roughly $150–200 kW/year vs $25–30 kW/year Texas rates,13 by using a physics-based view of network flows and AI enabled capacity trading strategies.

This enables smarter dispatch of large on-site batteries at data centers, timing charging and discharging to maximize market revenue while meeting compute load demand. This will improve economics of any distressed or standalone batteries near data centers, so those assets can reliably provide capacity and grid services that support data center uptime. They will also provide the optimization layer that lets batteries buffer gas turbines, covering fast ramps and shortfalls so data centers can access firm, responsive power even when turbines cannot ramp instantly.

Back to Rack City

Continuing on with our reconfiguration. We’ve covered power delivery and storage, let’s talk RACKS. With higher-voltage systems, racks become more efficient in a few ways: they waste less energy converting power, and they can support much higher power density. The physical and electrical design of the rack has to adapt to handle higher voltage safely and efficiently. Traditional AC racks operate at around 415V or 480V, usually handling 10–50 kW per rack.14 In those systems, electricity flows through the data hall’s power units and then into a power supply unit (PSU) inside the rack, which converts AC power into DC power that the chips can actually use. Voltage regulator modules (VRMs) then fine-tune that DC voltage before it reaches the processors.

When we move to 800V DC systems, racks can take high-voltage DC power directly skipping the old rack-level AC-to-DC conversion step. Instead, they use DC-to-DC converters built with advanced materials like silicon carbide (SiC) or gallium nitride (GaN) - the same tech used in solid-state transformers. These components are extremely efficient, achieving over 98% efficiency, which significantly reduces energy loss.15

Traditional racks with integrated PSUs must be redesigned to eliminate PSUs, freeing up to 60% more space for compute while reducing failure points. Power shelves and busways will also shift to 800V-compatible designs, often as sidecars, to handle doubled capacity via N+N redundancy without proportional copper increases (allowing for 45% less copper).16 That much power also forces tighter integration between power hardware and cooling (airflow channels, cold plates, clear paths for exhaust), which pushes a re-think of where power shelves, cabling, and other components sit in the rack.

Deep Dive into Cooling Systems

Get ready for an unhinged deep dive on cooling, one of the least understood but most important financial and operational drivers of next gen compute. As discussed in earlier sections computing is an exothermic process - the primary physical output of a semiconductor is heat. Yes, there is a lot of innovation happening on the chip side to produce chips that use less power, generate less heat or even no heat at all. You’ve probably heard of photonic or optical chips which use light from lasers as opposed the current regime of transistor based chips. There’s entropy-based computing, adiabatic computing, and many more experimental designs but we believe the path determinism and sheer capital allocated to this complex and tightly coupled and vertically integrated design and manufacturing ecosystem for a transistor based chip regime bends the arc of reality towards current chip designs deployed at scale for the next decade or more. So we will talk about heat mitigation once generated (downstream) v reducing chip heat emission (upstream).

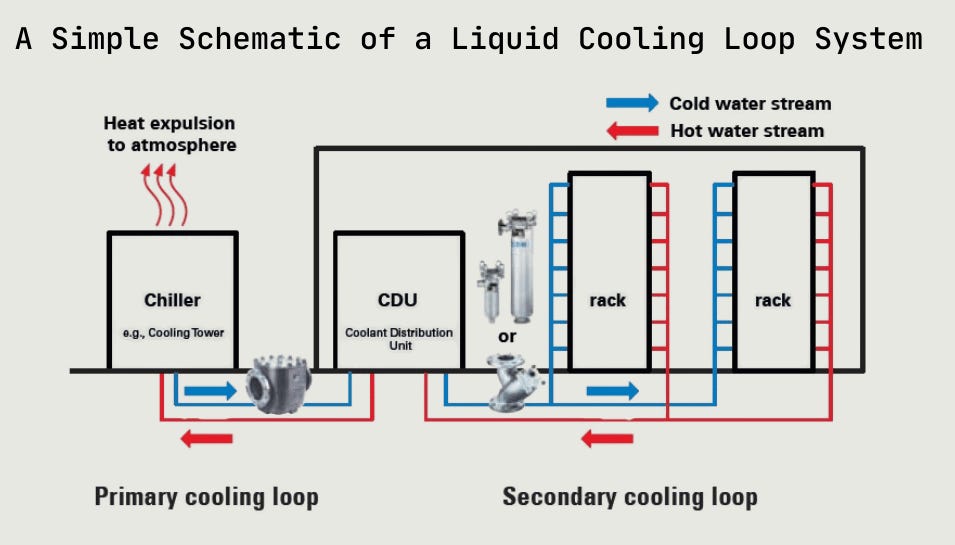

So we have a bunch of heat concentrated in increasingly denser racks. How do we remove this heat to prevent the racks and GPUs from melting? We use thermodynamics to design an efficient system for heat exchange - in this case, using a liquid medium. Here is a simple schematic of a data center cooling loop system deployed today:

Liquid cooling in a data center is essentially a set of coupled heat exchanger loops that move entropy from the chip junction out to ambient air using liquids with far higher heat capacity and thermal conductivity than air, with a substantial tradeoff - the infrastructure (pumps, heat exchangers, chillers, towers, controls) consumes substantial power to maintain flow, pressure, and temperature gradients and adds immense operational complexity.

The reason the industry has shifted to liquid cooling is about material properties and heat flux. Liquids like water, water‑glycol, or dielectrics can carry far more heat per unit of volume and per degree of temperature rise. As rack power density rises, liquid cooling can keep GPUs in the mid‑40s to low‑50s °C under load and even increase computational throughput. Physics do not allow for air cooling in these power dense environments.

Liquid cooling is already standard for H200, B200, and B300 deployments (Nvidia’s 2023, 2024 and 2025 vintages respectively), but every liquid cooled deployment still feels custom from the perspective of a data center operator (we talked about this with our data center operator who contributed to this report). A liquid cooling system requires chillers, pumps, tanks, and miles of piping in an environment where mistakes can cost tens of millions of dollars. Cooling systems are expensive and are facing their own supply chain shortages.

From our conversations, we’re within 12 months of truly streamlined solutions for next-gen systems. What the future brings: the incoming 800V architecture mandates 100% liquid cooling at 45°C inlets, with liquid-cooled busbars offering 20x more energy storage for stability. Row-based CDUs (cooling distribution units) integrate directly into the rack, replacing standalone systems and reducing water usage by allowing warmer fluids. Racks eliminate PSU fans, improving airflow and cutting energy for cooling by 20-30%.17 All in all, the reduced heat from fewer conversions (e.g., no reactive power losses) and fewer standalone systems (eliminating PSUs and VRMs) complement the liquid-cooled mandate of these denser racks.

It is important to get every aspect of a cooling system exactly right. The Uptime Institute reports that cooling systems accounted for 13% of datacenter failures in 2024.18 Frequent incidents involving cooling systems highlight the fragility of the status quo, from a cooling-related system failure impacting CME Group infrastructure at CyrusOne in Q4 2025, to a “thermal event” that triggered automatic shutdowns at a major Azure facility in Western Europe, to a February 2024 cooling-system failure that knocked out network access across 15 UNC Health hospitals. Streamlined solutions in liquid cooling are the north star and are coming soon, we hope.

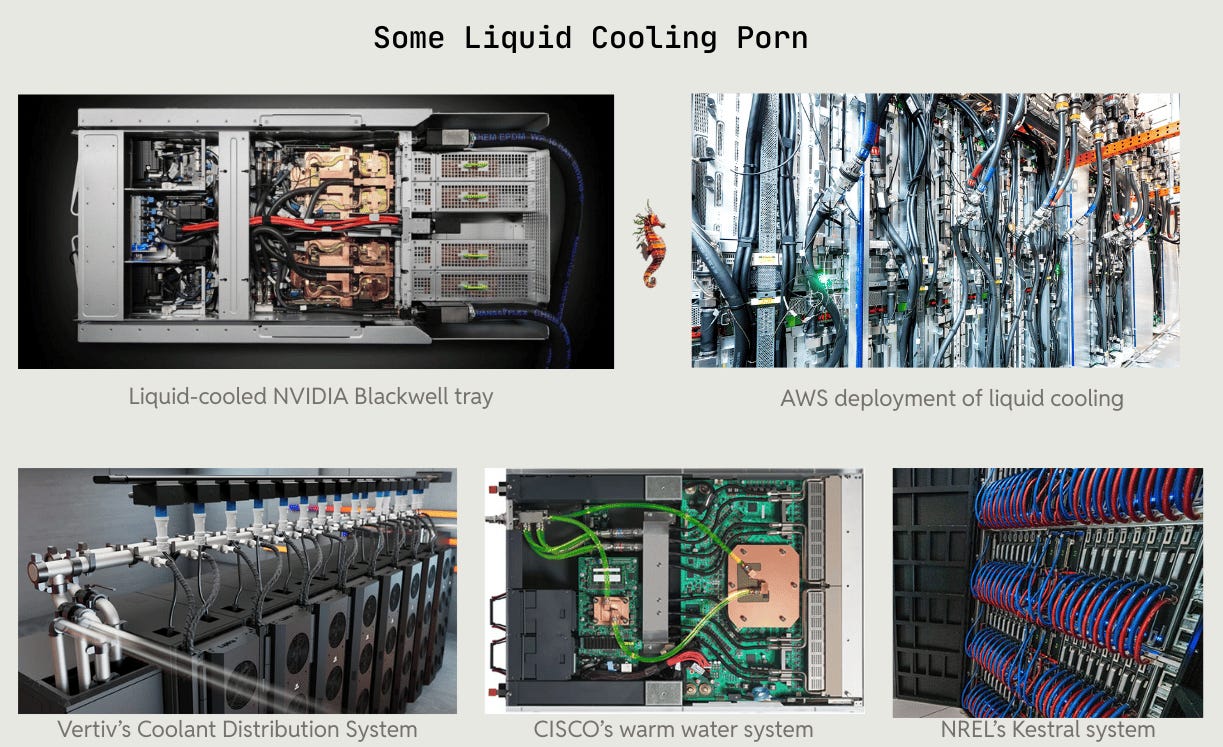

With that said we’d be remiss not to take a quick tour through the various adaptations of liquid cooling explored by the industry, each with their own cost benefit and very much in use for specific situations: Direct to Chip, Rear Door Heat Exchange, and Immersion Cooling.

Direct to Chip (D2C) Cooling and Chillers

Direct to chip cooling - the dominant liquid cooling mechanism for AI workloads - delivers coolant directly to the hottest components of the rack - the CPUs, GPUs and memory modules - via cold plates attached to them. The liquid absorbs heat and is pumped away to a heat exchanger or chiller for cooling before recirculation. Two phase and single phase D2C cooling systems use refrigerant and water-glycol mixtures as their cooling agents, respectively.

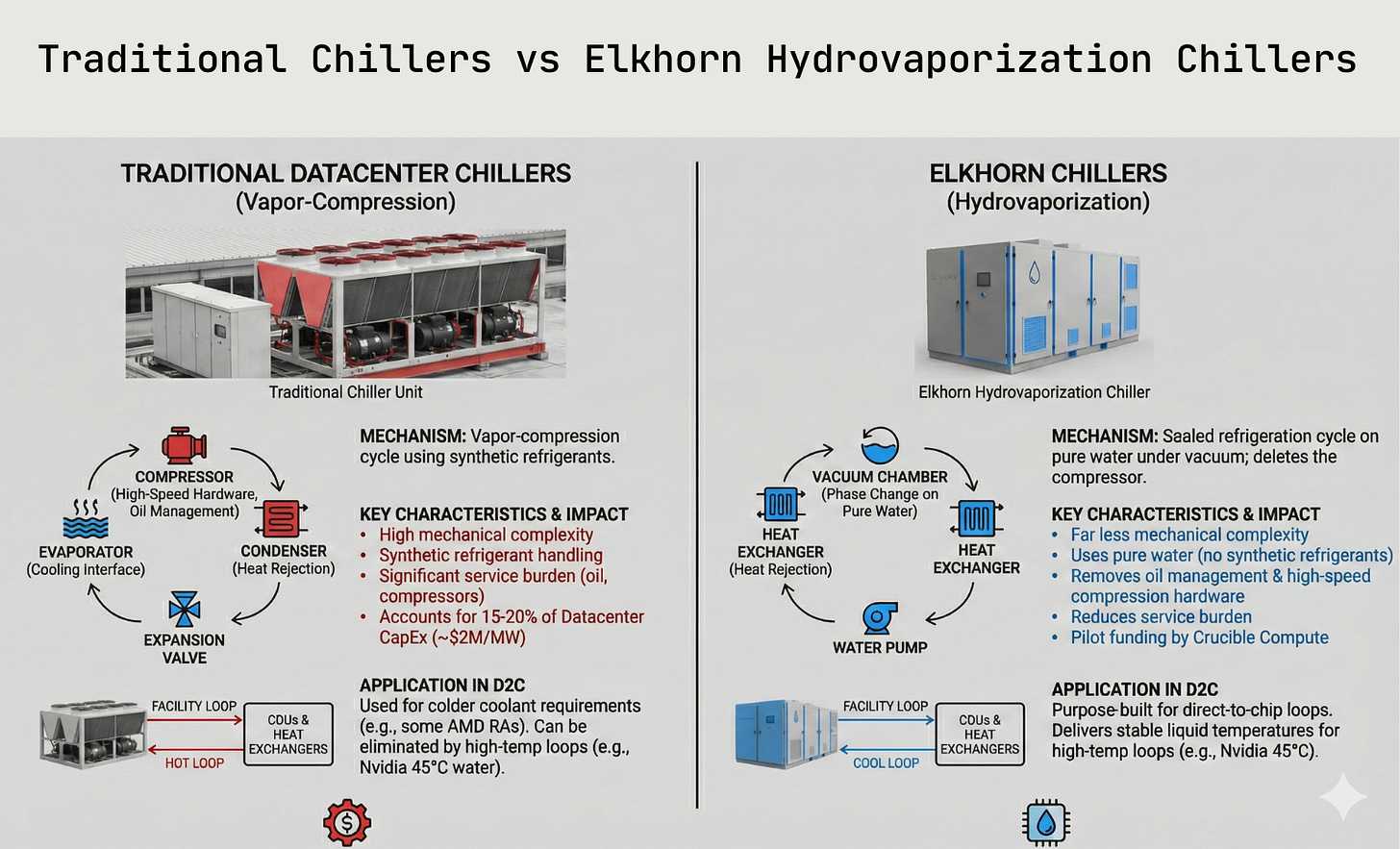

Chillers are used to keep fluids cool - who knew! - and account for 15-20% of datacenter capex at roughly $2M/MW give or take depending on model and scale. Nvidia’s use of 45°C water eliminates the need for chillers, though other OEM RAs like AMD still run on colder coolant and chillers. Nvidia achieves this through single-phase direct-to-chip cooling with higher coolant supply temperatures (45°C), which provides sufficient temperature difference to cool chips running hot.

Through our compute investment arm Crucible Compute, we are funding the pilot deployment of a new water based chiller purpose built for D2C loops. Elkhorn’s Hydrovaporization architecture deletes the compressor by running a sealed refrigeration cycle on pure water under vacuum, using phase change to move heat with far less mechanical complexity than vapor compression systems. In a D2C stack, it sits on the facility loop that feeds CDUs and heat exchangers, delivering stable liquid temperatures while removing the oil management, high-speed compression hardware, and synthetic refrigerant handling that dominate service burden in conventional chiller plants.

This is not a lab-only idea. Elkhorn has built and tested 36 physical prototype iterations, and in a production deployment at KRAMBU’s Newport, Washington AI data center the system logged a live COP of approximately 11.8, reduced cooling power to approximately 85 kW per 1 MW of IT load versus approximately 170 kW per MW for a traditional chilled-water plant, and improved observed facility PUE from approximately 1.18 to 1.09. For high density AI loads, that shows up as real capacity unlock, lower demand charges, and a smaller electrical and mechanical footprint for the same compute. For operators getting grilled in more ... shall we say, ESG-coded locales, the more immediate win is simple: eliminating high “global warming potential” refrigerants removes emissions risk, and cutting cooling electricity reduces the extra waste heat and upstream emissions that come from running the cooling plant itself.

Rear Door Heat Exchange (RDHx) Cooling

RDHx is a fascinating hybrid of liquid and air cooling: these systems replace or augment the rear door of a server rack with a liquid-cooled heat exchanger. Hot air from servers passes through the door, where it’s cooled by circulating fluid before being released back into the room. Systems can be passive (relying on server fans) or active (with added fans).

As legacy datacenters are primarily air cooled as discussed before, RDHx is a good fit for retrofitted sites, with the added benefit of no direct liquid contact with IT equipment. Cons, however are RDHx is less effective for extreme densities and still relies partly on air movement making this most suitable for gradual upgrades rather than a long term cooling solution.

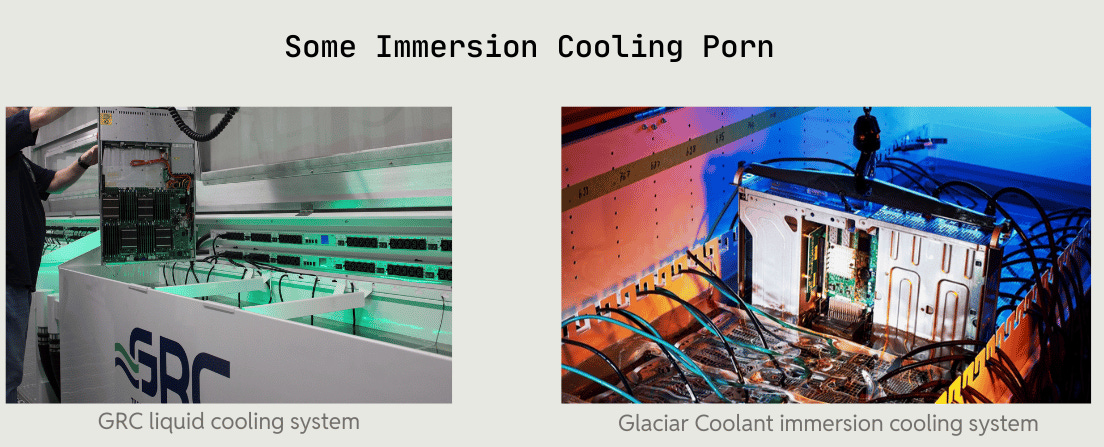

Immersion Cooling

First pioneered at scale in containerized bitcoin mining deployments, immersion cooling works by dunking chips into fluid. Uniform liquid contact with greater surface area than a loop system reduces hotspots and thermal cycling, which can improve reliability and allow sustained full‑power operation of high power density GPUs. Waste heat is at a higher, more usable temperature, which makes it easier to reuse for district heating or other processes when coupled to an appropriate secondary loop. Immersion cooling improves thermal headroom and reduces energy spent moving and chilling air, improving overall power efficiency and lowering cost.

However, immersion cooling has its own challenges. Physical access is harder: specialized technicians have to lift servers out of tanks, manage dripping fluid, and more. Vendor and warranty constraints make it difficult to assign chip failure liability to the operator v the OEM. Immersion also weakens the case for using GPUs as fungible collateral. Most data center deployments need significant leverage to achieve viable unit economics, with lenders having a lien on chips and equipment. Immersion hardware is a niche market and submerged GPUs have a somewhat illiquid secondary market and value is tied to an integrated system, so the GPU is not able to “pick up and redeploy anywhere,” which weakens its profile as generic collateral.

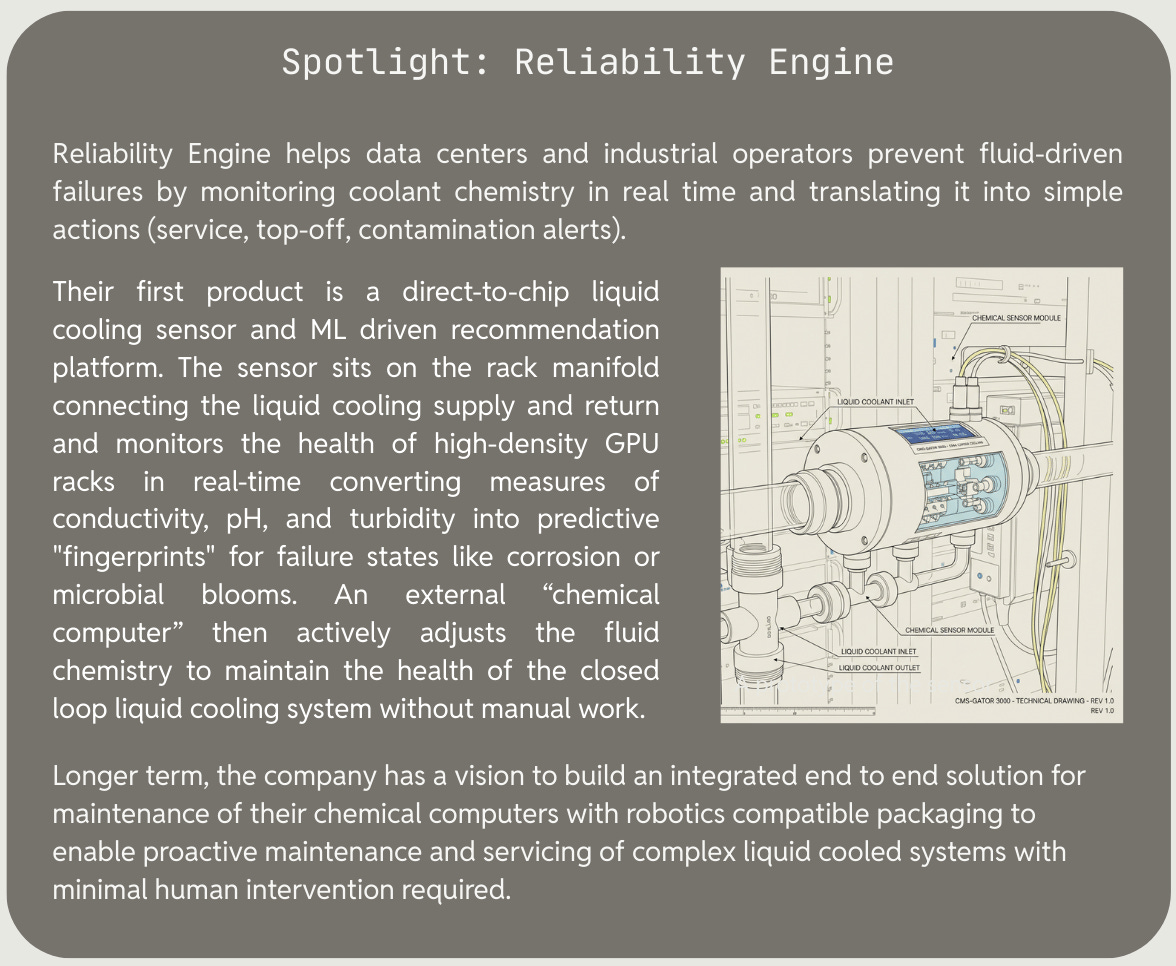

These are not the only innovations in cooling - we continue to track developments on the upstream cooling consumer - the chip itself - and the downstream mitigant of heat - the cooling system. One additional consideration that is not covered in detail in our reports but is a core area of interest for our venture investing is monitoring and maintenance of complex industrial systems like data centers. We are working at the intersection of multiple concurrent waves of technology, systems, and process innovation across energy, compute, robotics, and industrials. While the current narrative is focused on the immense capex of these systems, over time, deployed capex requires an increasing share of operational expenditure. One investment related to cooling sits at the intersection of technology innovation through intelligent chemical computing, systems innovation through advanced liquid telemetry, and process innovation through automated maintenance and servicing.

And so our cooling journey comes to an end, please excuse the cursory treatment of the topic which unfortunately did not result in brevity. Mi scusi. As you can appreciate, modern data centers are the aggregation of decades of weapons grade autism coupled with manic obsession across a wide range of complex disciplines to an exacting level of precision.

Monitoring & Maintenance: The Eternal Watch

So now you’ve got a bunch of really expensive gear that is very complicated, finagled together into highly interdependent systems with their own hardware and software, and not very fault tolerant (must operate in a fairly narrow temperature and condition range) sitting in a warehouse in bumblef*ck somewhere with thousands of kW of power flowing through it 24/7/365. How do you monitor and maintain it all so it doesn’t explode? Good question. I’m really so happy you asked. (A lot of people don’t which ???)

The coming 90x increase in rack density over the course of the datacenter’s lifetime creates a challenging task for GPU operators and owners. Equipment is expensive - a 1 MW cluster of brand new Nvidia B300s in reference architecture runs you around $40m in compute equipment alone. Preserving and monitoring this equipment is paramount to both owners and creditors of compute. With numerous hardware components included in a cluster, monitoring the health of an entire system within a single pane of glass requires integration with countless hardware manufacturers.

Aravolta, a Crucible portfolio company, wrote an excellent report on what legacy management systems look like and why better systems are needed for modern datacenters. As the team are builders of these very systems, we won’t reinvent the wheel and rephrase their words. Aravolta stands on the premise that modern DCIM must be built on these principles:

Real-time first: Sub-second data updates and instant alerting as the baseline, not a premium feature

GPU-native: First-class support for AI infrastructure with deep understanding of GPU workload patterns

API-driven: Everything accessible through modern APIs with excellent documentation and examples

An Asset API which collects and normalizes data across any vendor or protocol - from the switches, servers, PDUs, etc. This creates a single pane of glass operational software for data centers.

Cloud-native: SaaS delivery with no on-premise infrastructure requirements

Transparent pricing: Simple, consumption-based pricing that scales with your needs

Great UX: Intuitive interface that doesn’t require training courses, like so:

The team is delivering not only on this but, as the debate around GPU useful life continues to escalate, Aravolta are also providing telemetry data to GPU backed lenders and operators to provide full look through into the wear and tear of the cluster. We’re deploying the software on our compute cluster and look forward to sharing the observed data on our GPU utilization in order to contribute to the ongoing discourse around GPU life cycles in a constructive way. We continue to maintain that the question of GPU longevity is not a question of Michael Burry vs Coreweave but simply a question of how GPUs are used, and Aravolta provides a lens through which to measure and view this data.

In practice, the point of all this monitoring is to drive maintenance events. Telemetry, manuals, SOPs, and historical incidents get stitched into a shared context so the system can say, “This rack is running outside design envelope, here is the likely cause, here is the standard procedure, here is when you should fix it.”

That context flows into the operational tooling operators already live in, the ticketing and work order systems that manage incidents, changes, and scheduled maintenance. Instead of a firehose of alerts (many operators have told us they suffer from a deluge of alert fatigue), you get a queue of concrete jobs, each tied to a specific asset, priority level, maintenance window, and checklist. Over time, that loop between monitoring, context, and maintenance records becomes a living maintenance graph for the site, showing what work was done, how it affected failure rates and power use, and how hard you can safely run the hardware without blowing up your uptime or your balance sheet.

It’s all recursive loops of energy and atoms and information, running forever and ever in a warehouse somewhere you’ve never heard of, designed installed and maintained by engineers and operators who possess a level of maniacal obsession you’ve never imagined, and funded by technocapitalists with visions of a future we can’t see quite clearly.

Bars.

The End, for Real this Time

A key question to ask is how prepared the datacenter supply chain is for all parts of the transition discussed here. Nvidia’s Rubin Ultra GPUs and system (which is commanding these changes with its insane 1 MW peak rack density) will begin shipping in 2027, which, if you’re a multi billion dollar OEM, is tomorrow. Schneider Electric has committed to support 800 VDC via their compatible power supply unit (PSU). SuperMicro is actively developing solid state transformers, supercapacitor, and 1.1MW Kyber racks as part of their DCBBS (Data Center Building Block Solutions) ecosystem for Rubin Ultra’s launch. Both are a strong signal the industry is taking the call to action by Nvidia seriously.

Bottom Line: NVIDIA is forcing the entire infrastructure stack to evolve simultaneously - SSTs, supercaps, 800V DC, and liquid cooling all need to deliver on time for the 2027 Rubin Ultra revenue ramp. THE SPICE MUST FLOW! SuperMicro’s DCBBS approach could accelerate adoption by turning a “coordinate 5 vendors” nightmare into integrated building blocks for chip distributors. This is good news, but also entrenches moats further.

The risks are obvious but worth stating - new technology deployments are messy. As in the early days of liquid cooling when fluid seals commonly failed, pipes eroded, or power outages forced system failures, the introduction of new power systems won’t come easily. Solid state transformers, while faster and nimbler than traditional, are still new, expensive, and sensitive. Their interactions with the grid must be monitored closely, and the necessity for digital control introduces its own suite of cybersecurity hurdles to be tackled. The standardization of liquid cooling at warm temps by Nvidia is widely welcomed, and other OEMs would be behooved to follow suit. For example, AMD’s cooling architecture still commands cold temperatures and thus chillers, an added expense and waste of energy.

We’re excited to be investing across the gamut discussed here at both the early stage and in physical equipment for compute deployments. If you’re working at the intersection of these issues, please get in touch on email or X dot com. Our forthcoming report in this series will cover networking and orchestration hardware and software, switch nerds COME FORTH!

https://aiimpacts.org/global-computing-capacity/

https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/energy-and-ai-observatory?tab=Energy+for+AI

https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/ai-to-drive-165-increase-in-data-center-power-demand-by-2030

https://www.vertiv.com/en-us/about/news-and-insights/articles/blog-posts/bridging-the-present-to-the-future-rack-level-dc-power-distribution-for-legacy-ac-designs/

https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/energy-demand-from-ai

https://www.opencompute.org/files/OCP18-400VDC-Efficiency-02.pdf

https://www.snsinsider.com/reports/solid-state-transformer-market-2732

https://semiengineering.com/the-race-to-replace-silicon

https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-gallium.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10856355/

https://energyanalytics.org/the-battery-storage-delusion/

https://thundersaidenergy.com/downloads/supercapacitor-the-economics/

https://modoenergy.com/research/en/ercot-battery-benchmark-report-october-2025-battery-energy-storage-revenues-capture-rates

https://dgtlinfra.com/data-center-power/

https://navitassemi.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Redefining-Data-Center-Power-GaN-and-SiC-Technologies-for-Next-Gen-800-VDC-Infrastructure.pdf

https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/nvidia-800-v-hvdc-architecture-will-power-the-next-generation-of-ai-factories

https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/nvidia-800-v-hvdc-architecture-will-power-the-next-generation-of-ai-factories

https://uptimeinstitute.com/